Iraj E. Ghoochani

This essay serves as a supplementary reflection on my dissertation titled Bābā Āb Dād: The Phenomenology of Sainthood in the Culture of Dreams in Kurdistan, with an Emphasis on the Sufis of the Qāderie Brotherhood (Esmaeilpour Ghoochani, Iraj, 2017). (URL: https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/21528/) This work was completed at LMU München, Faculty of Philosophy, Science Theory, and Religious Studies. For reference, when I mention “dissertation” in this essay, I am referring to this specific document.

Abstract

This essay is about the rivalry between kings and poets within Persianate societies, illustrating the tension between the “word of power” held by rulers and the “power of words” wielded by poets. It posits that the nature of dreams differs significantly between members of the elite and ordinary subjects, reflecting their respective positions within the social hierarchy. Through an exploration of dreams, it asserts that the narratives of kings are imbued with authority and political significance, while those of ordinary individuals are bound by societal norms, often limiting their expression and interpretation. Drawing from hagiographical and ethnographical material, the essay contextualizes dreams as mirrors of the symbolic order, revealing how these narratives are homologous to the dreamer’s social identity. By examining the Kurdish dream culture, the study highlights the interplay between individual aspirations and cultural frameworks, illustrating that dreams serve as both personal expressions and reflections of broader societal constructs. Ultimately, the essay contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex role that dreams play in shaping identity and reinforcing social hierarchies within Persianate and Kurdish contexts.

Introduction: From the Garden of Night-tales to the Desert of Dream (ze bāgh-i gheṣe be dasht-I khāb)

Dreams hold a significant place in Islamic culture, often described as central to the spiritual and social fabric of Muslim societies. Iain R. Edgar emphasizes this in his observation that “Islam has the largest night dream culture in the world today” (Edgar, p. 1). Among the regions contributing to this rich tradition, Iran occupies a pivotal role. This prominence is intertwined with the legacy of Ibn-i Sirin, widely regarded as the founder of the Muslim tradition of dream interpretation. Interestingly, Ibn-i Sirin was the son of an Iranian captive taken during the Muslim conquest of the Persian Empire.

His influence endures today, as his dream manual remains a cornerstone of dream interpretation in Iran and Kurdistan. However, the origins of this manual are shrouded in ambiguity; it is likely a product of collective memory rather than his own authorship (Lamoreaux, p. 19). Despite this, Ibn-i Sirin’s name resonates strongly across Kurdish oral traditions. During my research into the Kurdish culture of dreams, every interviewee unequivocally identified Ibn-i Sirin as a “Kurd” (Esmaeilpour Ghoochani, 2017). This perception highlights the unique way his historical persona has been adapted to fit the region’s narrative needs.

Kurdish oral culture, deeply rooted in pre-Islamic traditions, often relied on archetypal figures to encapsulate and transmit its vast troves of lore. Ibn-i Sirin, as a historical figure from early Islam, proved an ideal vessel for preserving and conveying this legacy. While his actual authorship of a dream manual remains uncertain, his role as a symbolic figure in the Kurdish tradition underscores the interplay between oral history and cultural identity.

Dream Narratives in Persianate Societies

Dreams occupy a vital role in Islamic culture, deeply intertwined with oral and literary traditions. Ibn-i Sirin, the son of an Iranian captive, stands as a central figure in this tradition. His name is associated with the most influential dream manual in the Islamic world, though the manual itself is likely a product of oral transmission rather than his own writings (Lamoreaux, p. 19). The oral nature of Kurdish culture, in particular, shaped the transmission of his lore, embedding Ibn-i Sirin as an archetypal figure whose legacy continues to influence dream interpretation in the region.

The uniformity of early Muslim dream traditions, as described by Lamoreaux, highlights their enduring consistency. For example, the interpretation of symbols such as a frog has remained unchanged from the second to the fifth centuries A.H. and across vast regions, from North Africa to Iran (Lamoreaux, p. 104). This homogeneity suggests that the written texts of dream manuals are reflections of a robust oral tradition that preceded and paralleled literary documentation.

Night dreams and oral tales share profound connections, especially in Kurdish contexts, where dreams frequently feature as pivotal elements in storytelling. Both forms rely heavily on associative symbolism and occur in nocturnal settings, emphasizing their mutual role in cultural expression. Dreams often transcend the boundaries of day-to-day experiences, becoming precursors to poetic forms and creative intuitions. Annemarie Schimmel, a scholar of Sufi literature, highlights how dreams and tales in Persian and related literatures, such as Kurdish, Urdu, and Turkish, are deeply intertwined. She suggests that storytelling can transport listeners into a dream-like state, seamlessly blending the boundaries between narrative and dream (Schimmel, pp. 298–299).

This interplay is exemplified in iconic works like 1001 Nights and the tales of Scheherazade, where narratives extend into dream-like continuations, guiding the audience into a liminal space of imagination and slumber. The parallel between tales and dreams underscores their shared function as vessels for exploring subconscious realms and transcending linguistic and cultural boundaries.

The central premise of this article is that in oral cultures such as Kurdistan, the ontological foundations of dreams and stories are intrinsically linked. This shared basis offers valuable insights into the narrative structures of Kurdish prophesying dreams, hagiographies, and folk stories. A fascinating connection emerges between the concept of fate and the written word, evident in linguistic parallels such as the Persian sarnevesht and the Kurdish chārehnousa, both meaning “written fate (on the face or head).” This linkage resonates with Islamic philosophy, which delves into the relationship between fate (ghaḍā) and the written word (maktoub). While this philosophical perspective is only briefly addressed here, its relevance to the discussion is significant.

A key focus now is how societal hierarchies and social order are mirrored in dream narratives, particularly those involving kings or Sultans. These “royal” dreams are explored within the framework of Max Weber’s concept of sultanism. In his analysis of patrimonialism, Weber identifies sultanism as a form of administration characterized by extreme personal authority and control, leading to a system that is essentially arbitrary and often violent (Weber, 1922, p. 175). Weber’s choice to use the Arabic term “Sultan” reflects its historical roots, as this mode of governance finds its archetypal expression in the Near East (Chehabi & Linz, 1998, p. 6).

Dreams involving kings or Sultans thus serve as reflections of these deeply rooted societal structures, revealing the dynamics of power and authority within oral narratives. The interplay between fate, authority, and narrative underscores the profound connections between cultural traditions, philosophical concepts, and social hierarchies in Persianate states.

Inalcik also states this:

What Max Weber meant by Sultanism was originally derived not from Islamic precepts but from the caliphal state organization, which owed its basic philosophy and structure to the Byzantine and Sassanian heritage. This Iranian state tradition was transmitted to the Ottomans through native bureaucrats and the literary activity of the Iranian converts who translated Sassanian advice literature into Arabic. (Inalcik: 22)

This literary activity appears to exist in a symbiotic, if not causal, relationship with social hierarchy. Friedrich Engels, in his seminal work Anti-Dühring (1878), observed a causal link between “administrative regulations” and the emergence of “administrative despotism,” underscoring the interconnectedness of societal structures and governance with cultural expressions.

Inalcik continues with a synopsis of Tansar-nāme, a royal advice-letter from Sassanian times that is worth including here because it portrays the general social pyramid of a Persianate society as well as its social castes:

Man are divided into four estates…and at their head is the king. The first estate is that of the clergy…the second estate is that of military… the third estate is that of the scribes… the fourth estate is known as that of the artisans, and comprises tillers of land and herders of cattle and merchants and others who earn their living by trade…Assuredly there shall be no passing from one to another unless in the character of one of us outstanding capacity is found… The King of kings… kept each man in his own station and forbade any to to meddle with a calling other than that for which it had pleased God…to create him. He laid commands moreover on the heads of the four estates…All were concerned with their means of livelihood and their own affairs, and did not constrain kings to this by evil devices and acts of rebellion…The commands given by the King of kings for occupying with their own tasks and restraining them from those of others are for the stability of the world and the order of the affairs of men… He has set a chief over each estate and after him a trusty inspector to investigate their revenues. The King of kings has issued a decree to exalt and ennoble their noble families rank …By it he has established a visible and general distinction between men of noble birth and common people with regard to horses and clothes, houses and gardens, women and servants…(Inalcik: 22-23).

In this work, this pyramid, which is sharply peaked, has been considered as a highly polarized constellation of just two simple estates: the king and his subjects (roʿāyāʾ). All other castes, such as the clergy, sheikhs, and poets, are mostly like some starry points that fill the big empty space that exists between the king’s subjects in an extremely vast but leveled substrate of the pyramid and the king as its unreachable peak. The subjects are ‘leveled’ for similar reasons that Engels wrote in ‘Anti-Dühring.’:

The chiefs necessarily become the oppressors of the peoples, and intensify their oppression up to the point at which inequality, carried to the utmost extreme, again changes into its opposite, becomes the cause of equality: before the despot all are equal — equally ciphers. (Engels: 153)

This discussion examines Sultanism as an extreme form of patrimonialism and its enduring yet concealed connections to traditional systems of governance in the region, such as gerontocracy and patriarchy. These hidden continuities are revealed in historical narratives about the dreams of Sultans, where rulers frequently seek the guidance of wise mentors to interpret their visions accurately.

The analysis also highlights a fascinating parallel: the dual sovereignty of the Sultan as a despotic ruler and the poet as a revolutionary figure: One owns the language of power and the other one the power of language. This connection is vividly illustrated in the story of Nāli, the most renowned Kurdish poet of the Sorāni dialect, spoken widely in Sanandaj. The dynamic between the king and the poet underscores the interplay between political and poetical authority—between the domain of deeds and the realm of words (cf. Koschorke & Kaminskij, p. 12). This duality fosters a unique form of hermeneutics, where the condensed power of language bridges the worlds of politics and poetry, allowing them to coexist in a symbiotic relationship.

This article seeks to redefine the categorization of Oriental dreams by incorporating the social hierarchy and class of the dreamer. While the conclusions are based on “inductive inference” and remain subject to further proof, the emerging framework broadly identifies two categories of dreams:

- The subjective dreams of the king/Sultan, and

- The dreams of the king’s subjects.

Nāli: A subject in love with Queen

عومـرێکـی درێـــژە بەخەیاڵی سەری سوڵفـــت

سەودا و پەرێشانــــم و، ســـەودایـەکی خــــاوە

ʿomrbeki darbeyja bi Khiyāli sar-i zolfat

Soudā wa parishanam wa soudayi ki Khāwa

L et my life drift away, lost in the dream of your flowing tress,

I am enthralled, disheveled—a dreamer, consumed by this tender madness.

—Nāli

Here, Nāli has created a beautiful play on words, linking his unstable and melancholic state of mind with the disheveled state of his beloved’s hair. He also connects the black color of her hair with the word “soudā,” which means enamored, insane, melancholic, and also reminds one of the word “sawād”, or darkness. All of these wordplays are linked to a “night dream” and “sleep,” which are referred to by a single word in Kurdish: Khaw.

Kurdish folk tales exhibit many parallels with the folk traditions of other Iranian cultures, including those of Luristan, Azerbaijan, Gilan, and Mazanderan. Although most Kurds live in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, and are not directly associated with Iran, their language is Iranian, and their cultural affinities align more closely with Persian traditions than with Arab or Turkish influences, particularly in the realm of folklore (Tofiq, p. 5). Kurdish scholar Iraj Bahrami underscores this connection, asserting that an understanding of Persian poetry is indispensable for appreciating Kurdish poetry (Bahrami, p. 178). It is important to note, however, that the narrative forms found in Persian folk tales are not unique to Kurdish culture. Instead, the bureaucratic literature of the central Persianate state has historically interconnected various folkloric traditions across Persianate societies, known collectively as adabiyat-i ‘amiane (Chipak, p. 77).

Conversely, the influence of Kurdish oral literature on Persian literary traditions is noteworthy. For example, in the first chapter of the dissertation, the Kurdish story of Shirin and Farhad was shown to have left an indelible mark on one of the most esteemed works of Persian classical literature. This illustrates the rich exchange of narratives between these interconnected cultures.

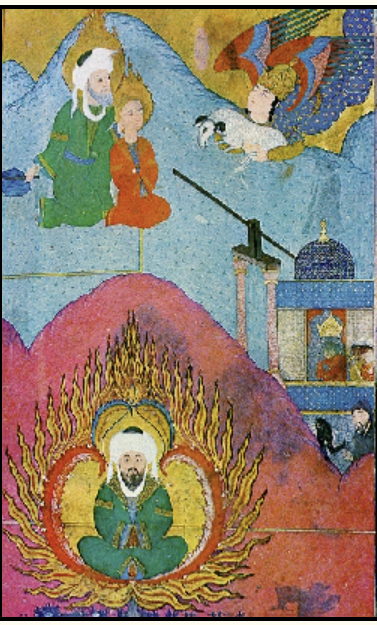

Dreams play a pivotal role in Kurdish storytelling. It is exceptionally rare to encounter a Kurdish narrative in which dreams do not serve as a decisive element. The functional use of dreams as a narrative device has been explored in the dissertation through an anthological review of classical stories, including the prophet’s nightly ascension (miʿrāj). However, this narrational strategy is not limited to classical tales; as we will observe, it also reemerges in modern reinterpretations of the story of Shirin and Farhad, showcasing the enduring significance of dreams in Kurdish cultural expression.

Nāli (1797–1855), a renowned Kurdish poet, is credited with adapting the traditional Persian poetic meters to the southern Sorani dialect of Kurdish, which is widely spoken in Sanandaj. He is celebrated as the founder of cultivated poetry in Sorani and has “contributed immensely to making Sorani the literary language of southern Kurdistan, encompassing much of present-day Iraq and the adjacent districts of Iran” (Encyclopedia Iranica, Nāli). Nāli lived during the reign of Khosro Khan Ardalan, ruler of Kurdistan, and his poetry reflects the vibrant cultural and political milieu of the time.

Nāli is also noted for composing what is believed to be the first radical erotic poem in Kurdish literature. The central figure of desire in this poem is Mastoure Ardalān (1805–1848), a princess, the wife of Khosro Khan, and the most famous Kurdish poetess of her time. In this work, Nāli vividly describes a dream in which he experiences an intimate encounter with Mastoure, employing a richly symbolic and poetic language to narrate the affair. Again the same triangle of key personalities that was in the story of Shirin and Farhad is repeated here. khosro khān-i Ardalān is comparable to the Khosro and the role of Nalī is comparable to Farhad as an ordinary person who comes from a lower class but is so brave and bold to express his love for the wife of the Khosro the king: Shirin/Mastoureh.

Despite Nāli’s close relationships with the princes of Kurdish principalities, such as those of Ardalan in Persia and Baban (see Encyclopedia Iranica), he himself was not of royal blood, and little is definitively known about his familial origins. His bold artistic endeavor, addressing such a sensitive subject, was a risky social and literary act that could have invited severe repercussions, particularly revenge or punishment from the ruling elite. However, Nāli avoided such consequences by framing the episode as a dream, leveraging the cultural and religious understanding that dreams are beyond one’s control.

In Muslim societies, dreams hold a special place, often considered a realm where sinful scenes or actions can be “seen” or “committed” without moral culpability. This societal tolerance for the contents of dreams provided Nāli with a protective pretext, allowing him to push artistic and cultural boundaries in ways that might otherwise have been unacceptable (refer to appendix of my dissertation[1]).

In Kurdish literature, the pivotal role of dreams persists well into the modern era, encompassing a wide range of functions, including the strategic use employed by Nāli to bypass the societal norms upheld by “the big Other” and avoid the punishment of a despotic ruler. This “big Other,” an external authority that enforces societal norms, is effectively realized in the figure of a despot. Similarly, in Freudian terms, the dream’s essential function is to navigate the super-ego by allowing repressed desires to surface in a disguised form within a dream narrative or poem. What is particularly striking in Nāli’s poem is how its structure aligns with Freud’s Oedipal triangle. The narrative revolves around three fundamental agents: the father (the king or “name of the Father”), the mother (the queen or the alluring object of desire, often symbolized by figures like Shirin), and the desiring subject (Nāli or Farhad). This configuration underscores the deep psychological and narrative underpinnings of the story.

Nāli’s conscious use of the dream-work as a narrative strategy reveals a sophisticated transplantation of the dream’s unconscious mechanisms into the realms of poetic and political discourse. By framing his poem as a dream, Nāli mirrored the unconscious processes of a night dream in his art, allowing him to express desires that would otherwise be socially or politically unacceptable. This deliberate act of creative subversion exemplifies how a poet can navigate and challenge repressive norms.

The strategy Nāli employed finds parallels in the broader Iranian literary tradition, which is rich in techniques for circumventing censorship and repression. A notable example is Kellile wa Demene, an ancient Iranian-Indian collection of tales, akin to 1001 Nights, where political commentary is cleverly “mouthed” by mute animals (ḥeywānāt-i zabānbaste). By presenting political discourse as innocuous, fabulous anecdotes, these works effectively deflect scrutiny while preserving their subversive messages. Nāli’s usage of the dream as a vehicle for artistic and political expression stands as a uniquely Kurdish adaptation of this timeless strategy.

Nāli’s poetry is notably influenced by the style, semiotics, and hermeneutics of the Persian poet Hafiz. Despite Hafiz’s reputation as a counter-culture poet (Hāfizi malāmati), Nāli diverges from Hafiz’s methods in a significant way. While Hafiz employed bilateral opposite meanings—‘primal words’—or voiced his dissent through the perspectives of marginalized religious minorities, he never utilized the strategy Nāli adopted. Instead, Hafiz’s subtle insubordination toward orthodox religion and authority was woven into complex layers of symbolism.

In contrast, Nāli’s use of a dream as a narrative pretext to construct a subversive discourse highlights the elevated role dreams occupy in Kurdish culture. This strategy, which allowed Nāli to express repressed desires or rebellion without overtly confronting societal norms, underscores the authoritative position of dreams among the Kurds. While the societal function of dream narratives is particularly prominent among Kurds in Iran, the broader Iranian linguistic tradition is marked by the use of primal words. This linguistic feature reflects the philosophical roots of the Iranian and Islamic “philosophy of meaning,” where words are seen as Decalogue, divine decrees, or commands from an absolute source, such as a ruler in communion with the occult (gheyb) and the absolute (moṭlagh).

This sense of absoluteness inherently generates its opposite—resistance—within the subjective consciousness of those bound by the language. This resistance often pushes language into a state of Ausstand—a strike-state of meaning—where the speaker’s true intent remains obscured, shrouded in ambiguity. Nāli exemplifies this linguistic duality in his famed Qasidah of the Wet Dream (ghasideyi ʾiḥtelāmiyah), where he boldly and transparently transfers the function of dream-work onto the narrative of a dream—one that he likely never experienced. By framing the poem around a wet dream, a culturally strategic choice, he circumvented societal blame or punishment under Islamic shariʿah, as wet dreams are involuntary and thus not considered sinful.

This calculated use of the wet dream to depict carnal desire and a symbolic relationship with the “mother” figure (the queen) illustrates the poet’s rebellious intentions camouflaged within the safety of dream narration. Moreover, as noted earlier, the capacity for dual interpretations—where one narrative simultaneously suggests compliance and dissent—is a hallmark of Iranian languages. This linguistic trait allows speakers to craft subversive statements while avoiding retribution, leveraging the creative and oppositional potential inherent in the language itself.

The concept of “primal words” inherently carries an element of rebellion, pointing to a “deferred signification” (in a Derridean sense). This deferral suggests a secondary intention within the word—one that stands in stark opposition to its conventional meaning. This phenomenon reflects the dual identity of intention and expression, or the distinction between the writer’s subjective intent (the internal, mental intention behind their words) and the act of writing itself (cf. Bornedal, p. 21). The latter, like any communicative act, requires a reflective “Other,” whose tolerance and interpretative capacity inherently constrain what is written.

In the realm of “primal words,” this secondary intention emerges as a silent interplay between the writer’s subjective mental life and the “big Other,” the external authority or societal norms that govern discourse. This interplay aligns with Lacan’s notion of the unconscious—not as an inaccessible realm but as an integral part of our everyday language, manifesting in the automated forms and clichés of daily speech. Lacan’s concept frames unconsciousness as a transparent camouflage for the second intention, embedded within the discourse of the Other.

To illustrate this further, it is useful to revisit Levi-Strauss’s definition of the unconscious. His framework situates unconsciousness as a dynamic system of symbols and structures that operate within, rather than beyond, the reach of their agents. By drawing on these insights, we can better understand how “primal words” function as a site of subversion, allowing suppressed or secondary meanings to surface within the confines of conventional language and societal norms.

What is called unconsciousness is merely an empty space in which the ‘symbolic function’[2] achieves autonomy” that is to say a space where “symbols are more real than what they symbolize”( Roudinesco, 1999: 211)

These built-in automated facilities are the effects of the way that the symbolic order[3] ( or ‘order of culture’ to speak more anthropologically) has been organized, that is, the language has inherited these features from the symbolic order because the ‘symbolic’ itself is nothing more than a language-mediated ‘order of culture’. Then it is through this features that the law can be interpreted differently. The effect of this interpretability (ghābeliyat-i taʾwil) , is to be seen in many stories of 1001 nights and other Oriental fables (including Iranian and Kurdish) and also in the historical hagiographies written for the early caliphs of Islam (see: Ahmadvand, 2008), in which the appliance of shariah or the law of orthodox Islam -which is supposed to be directive and unchangeable- is itself a function of a utilitarian reading of the law by a despotic king or ruler (ḥākim, a word that stands both for a ruler and a judge: A non-accidental coincidence). Conversely, there always remains the possibility for a person who has his head on the headman’s table open to bring the ruler into laugh with a joke or an anecdote and become forgiven of his trespasses[4]. The story of Shahrzad is itself a story of a woman who escaped her bad fortune by postponing this fortune for a night by narrating fabulous entertaining stories for 1001 nights. In our case, there was possibility for Nāli to portray obscene erotic scenes with the wife of the ruler and meanwhile stay free of punishment because all that he has written was what he had seen innocently in a dream on which he had no control.

As stated, this creative use of dream narrative for a conscious use of ‘dream-word’ in the day-time by a Kurdish author, implicitly reflects the authoritative importance of the dreams among the Kurds. No wonder that both the first Kurdish short story la khaw maw (in my dream) (See Safariyan & Sajadi: 87) and the first modern poem in Kurdish literature khow-i bardīnah[5] (stone dream) are related with dreams.

According to these accounts, it is sensible to have a short review on those oral narratives in Kurdistan which have a lot in common and coincidence with the Kurdish dream narratives. This coincidence comes from this fact that narrating a dream, as an act of speech, is rooted in the oral culture but meanwhile and reversely, it could also serve as a root by providing the oral culture new food especially when a dream becomes ‘true’[6](rāst dar ke). Every time that a dream bring itself into fruition a big amount of spectacular sayings would arouse around it and everyone tries to add some anecdotic details to it. In every renarration of the dream-story it becomes a little bit spiced up but meanwhile refined and constructed. This construction outlines the way that the dream is discharged from the world of dreams (ālam ol-aḥlām) to the world of reality. That is there is a common and collective intention to tie a dream successfully to the events of the daylight. Thus, more generally, a dream is a kind of prophecy or sign (ayat) both ‘from’ and ‘of’ the other side thrown to the real world. The normative access to this dream or sign is conditioned via a tradition and signification system in which a dream should be narrated and interpreted. Every sign is restricted to its possible meaning arranged in the Islamic dream manuals (above all the book of Ibn-i Sirin) as a table of signification. But notwithstanding this directive straight system of signification, the dream’s potential for authenticity does not lie absolutely in the dream itself (In its elements and their inner potential for being fit in a correct narrative form and so on..) but the dreamer (his/her social status, age and so on..) is the most determining criterion for the truth-value of a dream. For example and as we will see through several examples, a dream of a despot ruler is always ‘authentic’ in this sense that it is always ‘interpretable’ because it comes out from the lips of the ‘absolute’ that is from the domain of all possibilities and hence they do not need to follow the suit of a former forms of narrativity. On the other hand, narrating an out-of-genre dream narrative by a normal subject entails a lot of information that is in a reciprocal relation with its authenticity or probability[7]. Then in a Persianate context, it is of highest importance to ask who has seen the dream?

The success of a dream for consigning itself to history and being re-narrated and circulated among the people is strictly dependant on the status of its dreamer. In a reverse way, whenever a dream becomes ‘true’ that is becomes realized in the same way that was seen or interpreted through a dream, it abruptly brings a large status for the one who has dreamt it. The case of children is exceptional because their spirit is still not contaminated with the worldly matters as the social status. These two, the truth value of a dream and the social status of its dreamer, are strictly related to each other. The lesser the probability of a dream to become true, the higher is -or would be- the status of its dreamer and in some extreme cases it would be taken as a miracle (khāregh-i ʿādat) or an extraordinary occurrence (vāggheʿi) and would find its place in the body of oral stories as a seed that would grow and spice up in many different details and through the process of its circulation (See the miracle of Karjou in the film #1[8]) .

Conversely, when someone claimed of being in contact with divinity such as what happens in a revelation or ascension he/she might be asked for a miracle as prove:

But they say, “[The revelation is but] a mixture of false dreams اضغاث الاحلام ; rather, he has invented it; rather, he is a poet. So let him bring us a sign just as the previous [messengers] were sent [with miracles](Quran, 21:5).

As we will see in the coming passages hearing revelation and saying poetry as well as seeing false dreams اضغاث الاحلام and doing miracles are issues that usually appear together in hagiographies and stories told in the oral culture.

Narrating a dream and narrating a story in an oral culture are both based on a transaction of meanings between people who are engaged in the production of those meanings. Then alike to what Geertz has argued, “culture is not something imposed on people, but it is created and re-created through their involvement in social relationships and through social interaction[9]”.

In the process of circulation and re-narration of the new dream-story, old and new will fuse together into an indissoluble unity in a way characteristic of 1001 nights or every oral literature with an ambiguous origin. It is rather a process of evolution that covers bands of centuries and sometimes reappears again in its very arrangement in the modern era as like the reappearance of the so called Oedipal triangle between the king (Khosro), Shirin and Farhād in the story of Nāli. Through this general amalgamation of every new dream story and the old similar stories in an oral culture like Kurdish, ‘dream’ and ‘story’ both find the same ontological basis for their existence. This common ontological basis leads us to a study of the Kurdish oral literature and folk stories as the main resources and models for structural layout of the Kurdish dream-stories[10].

What is common between the folk stories and dreams, in fact, is the (story)teller who is not usually a literary person and belongs in the most cases to the lower social strata: to the common people. (cf. Bakhtin, 1984: 191-2) just like those who usually commit a miraculous deed or khawārigh (self- torturing ritual)in the convents (see also van Bruinessen: 309 ff.). Further studies of stories in the religious books and religious dreams will reveal that how these two (khawārigh and dream) are congener.

This kind of text analysis of the religious books would be not so far from ethnography because to do ethnography is a form of literary criticism “like reading a manuscript”[11] (Geertz 1973, 10). Here we make an ‘interpretation of cultures’ out from the ‘interpretation of dreams’, taking distance from the functionalists and instead come closer to the arguments of Clifford Geertz for what the he thought that a study of culture should be about. There are some theoretical outlines taking a dream as a text showing that the analysis of dream-elements is basically nothing more than a text analysis. That is a dream is a symbolic text that should be decoded. The keys of this coded language is given in the dream manuals and dream look-up tables in Islamic oneirocritic books (above all in Ibn-i Sirin’s book of dreams) where themselves are extracted from the religious books above all the Quran as the spoken words of God (Kalām ol-llah). Then a deep description of dreams in a Muslim, Sufi milieu calls for a deeper understanding of Quranic language and this itself raises some unavoidable philosophical discussions and preliminaries i.e. the strange relation between the ‘word’ and ‘flesh’ in an Islamic system of knowledge.

From the genuine world of ‘imperative’ (ālam-i ʾamr) to the illusive world of ‘creation’ (ālam-i khalgh)

Morgh bar bālāwa zir-i ān sāye-ash

Midavad bar khāk parān saye-vash

Ablahi ṣayād-i ān sāye shaved

Midavad chandānke bi māye shaved

Bikhabar kān ʿaks-i morgh-i havāst

Bikhabar ke aṣl-i ān sāye kojāst

The bird is above, and its shadow

is running bird-like below on the earth.

A fool becomes the hunter of that shadow

Running so much that he runs out of breath.

unaware that this is the reflection of the bird above

unaware of the origin of this shadow.

—Rumi

There is a general consensus on the stereotypical nature of dream narratives and it seems that every dream should be cast into the prescript forms of a narrative to be accepted by the society as an authentic true dream, but, what is astonishing is the fact that if someone faked up a dream story or a vision that its form matches with the form of meta-narratives of the dreams of a Muslim it would have the same phenomenological effects of a genuine dream[12].

The classical and Quranic example of this magical power of suggestion that lies in the dream narrative (and not necessarily in the dream) is the faked dream of one of the two co-prisoners of Joseph the prophet who narrate their dreams for him in the prison. Joseph interpreted this cooked-up dream as a foretelling of the dreamer’s execution. An accident that has been fulfilled although it was not ever seen by that person and even when he become repentant of narrating that false dream Joseph answered that there is no way back and “the matter was already been decreed”(Heravi: 511-2):

O two companions of prison, as for one of you, he will give drink to his master of wine; but as for the other, he will be crucified, and the birds will eat from his head. The matter has been decreed about which you both inquire. (12:41)

Joseph has used the same words ghaḍā al-ʾamr (to decree an imperative) used by the God in the following verse:

Originator of the heavens and the earth. When He decrees a matter, He only says to it, “Be,” and it is. (2:117)

This important verse relates the ‘flesh[13]’ as what is seen in the real world or world of creation ālam-i khalgh (also known in Islamic philosophy as ālam-i koun o fisād which means the ever-changing world of creations) to what had been decreed in the world of ‘words’ or the world of’ imperative’ or ʿālam-i ʾamr (also known as ālam-i kon or roughly ālam-i ʾasmāʾ)[14] . Rumi writes:

اسم هر چیزی بر ما ظاهرش

اسم هر چیزی بر خالق سرش

نزد موسی نام چوبش بد عصا

نزد خالق بود نامش اژدها

Our names of things convey the way they are seen

Their inner natures are what God’s names mean

For Moses simply called his stick ‘ a rod’[15]

While ‘snake’ was what had been assigned by God. (Rumi (Mathnavi, Book one, Story of Lion and Rabbit (translated by Mojaddadi: 79))

Then in this philosophical system, every ‘thing’ in under-heaven is a logical analogy of a name (ʾism), word or logos (λόγος) once called or said in the form of an imperative in ālami kon and inversely every ‘thing’ is a allegory (tamṯīl) of its name from which it was once called or named[16]. This Islamic-philosophy has tied itself firmly with the eidos of Plato after the translation movement of the Muslims in the Middle Ages (see Jamalpour: 343 ff.) with a large influence on Islamic Sufism and lranian Literature as like Rumi’s poem brought above as an epigraph.

Then the unchangeable world of words in Islam finds its analogy with the Plato’s theory of ideas known in Islamic philosophy as alam-i miṯāl. Moreover, it is utterly ‘logical’ that in Arabic Islamic literature there is just one word for both allegory and analogy: tamṯīl.

It is according to this philosophical groundwork that in the Islamic culture of dreams one may recognize a direct relation between what one sees as a vision (notwithstanding made-up or actual) and what should happen. Schimmel has also noticed that these made-up visions may reveal the suppressed wishes and hopes of their creators (cf. Schimmel: 325). An aspect that has no essential difference with western psychoanalytical theories of dream. Allegorically one can conclude that a dream is both a mirror of the decreed facts in the future and also a mirror of soul. This latter aspect of dreams which serves as the soul’s mirror has a therapeutic and diagnostic usefulness similar to the treats used in psychoanalysis but it is not a matter of direct emphasize and discussion in an Islamic culture in which individuality[17] is not celebrated.

Iain R. Edgar has also described this:

…while in Freudian theory the latent meaning of the dream is usually perceived as a repressed sexual desire and deciphering this latent meaning is part of the purpose of psychoanalysis, such encoded sexual dreams in Islamic dream theory are not considered important, as desire is seen as appropriately regulated through the Shariʿa law, based on the teaching of the Quran and the hadithes. (Edgar: 113)

In a Muslim society and specially among the Sufis, the individualistic needs and traits are read as different attributes of nafs or ego, an elusive and illusive entity that should be controlled if not eliminated. Ego for a mystic has not an existential essence and hence, it is of no importance (though it has immense virtual effects on psychological state and social status) and because of its illusive nature, it is considered as an obstacle or veil (ḥijāb) in the way of God (ḥaq= truth). The removal of this veil is the only and life-long duty of every Sufi. The full elimination of nafs is the ultimate – and almost unreachable[18]– goal of a Sufi. It is usually named as Jihād-i Akbar or the biggest Jihad to allude to its hardness. In the allegorical language of Sufis, the soul itself is considered as a mirror (expressed in many poetical combinations and forms such as āʾīne-yi rouḥ, āʾīne-yi jān, āʾīne-yi ghalb, āʾīne-yi dil, āʾīne-yi jām, jām-I jahān bin etc. ) will and nafs is what that makes this mirror contaminated and dusty so the images in this mirror (God’s will (ghaḍāyi ʾilāhī)) look distorted and vague. All that one sees in the mirror of the soul (i.e. in a dream) is a direct reflection of the God’s will or message. The clarity of this message is dependent to the degree of which the soul has retained itself clean -through devoutness, piety, recoursing to a sheikh, doing some techniques and disciplines as like commemoration, ritual dances and so on… Rumi writes:

Love wants its tale[19] (sokhan)revealed to everyone

But your heart’s mirror won’t reflect this sun

Don’t you know why we can’t perceive it here?

Your mirror’s face is rusty, scrap it clear! (Rumi, masnavi, translated by Mojaddadi: 6)

In short, when a Sufi is advanced in his/her way (ṭarighat) he/she will see clearly the truth and his/her soul reflects nothing than the will of God. Otherwise the uncanny images in this mirror (i.e. the objects seen in a dream) are rather the reflections of the obstacles that the Sufi has in his/her way. His /her unfulfilled missions for elimination of nafs as the source of desires (hawāhāyi nafsāni). In such a case, instead of clear images, the dreamer for instance sees his/her own ego or better to say a composite structure with different degrees of truth and falsity, just like the images that one sees in a dusty mirror. For a new apprentice (murid), the Sufis’ culture of dreams has a lot to share with a Freudian theory of dreams. By hearing to the dreams of his pupils, a Sheikh understands of the obstacles through which they should battle their way for reaching God/truth (ḥaq) and gives each of them the necessary instructions of how to evade the involved desires of nafs.

As stated before, inside this culture of dream, for a clear mirror of soul, a dream entails a prophesying capacity that could clearly reflect the will of God. This (in contrast to the last case in which a dream was considered as a set of imaginative reflections seen from the dusty mirror of the dreamer’s soul) may lead us to a crucial difference and diffraction from a ‘western psychological theory of the night dream’ and an Islamic theory. The difference lies in the big shift of focus from the ‘dreamer’ into the ‘dream’. The language of the dreamer (as a negligible servant of God (bandeyi khodā)) functions like an empty container for the full language of God spoken in a dream. What is said in this full language is ‘decreed’ and would be happen. The real world follows the true word of the dream like a shadow. What is important here is this fact that this absolute fullness and emptiness (and similarly the decreed and deliberate (jabr o ekhtiyār)) are coined with each other as two facets of the same fact whose understanding is subjected to a “thick description”.

Schimmel has also related the foreboding aspect of dreams with alam-i miṯāl or the (Platonian)world of ideas and the fate of the human that is prescribed in Loh-i maḥfouẓ (ibid). Loh-i maḥfouẓ or the “protected board” (Wohlverwahrte Tafel) (Quran 85:22) is a board on which God has “written” all that is happened and should be happened with the holy feather (ghalam) (Quran 68:1). Many Muslims even think of a special sort of matter for it embodied in a white pearl (dorratol-beyḍāʾ) that has covered everywhere from west to east and from earth up to the heaven (cf. Wolf: 3) some others think of it of this very world in which all of our deeds remain perpetually in the form of its effects (to read more about Loh-i maḥfouẓ and its relating highly controversial discussions see: Kalantari: 117ff.).

In the 5th chapter of my dissertation, the relation between ‘the word’ (kalame) and ʿālam-i miṯāl in an Islamic context is discussed and it is tried to show that in this context, a ‘word’ not only works as a model or idea for the materialistic matters or ‘flesh’, but also they have a kind of indexical relation with each other like the relation between a body (accordingly word) and its shadow (flesh). Schimmel has outlined a parallel relation between the world of dream (ʿālam-i Royā) and ʿālam-i miṯāl :

…was hier im Traum geschah, war nichts anderes als was schon in der höheren Welt bestimmt war, auf welche Weise auch immer man diese höhere Welt definiere – ob es die Wohlverwahrte Tafel war, auf der seit Anbeginn der Welt alles, was je geschehen sollte, in dem menschlichen Verstand unzugänglichen Lettern geschrieben ist, oder ob es die Zwischenwelt, ʿālam-i miṯāl war, wo die Urbilder aller Dinge lokalisiert sind. (Schimmel: 325)(should be translated in English)

The signification system between the ‘word’ seen in the world of dreams or ʿālam-i Royā and its ‘flesh’ or shadow as its decreed effect in the world of reality is direct and straightforward. For example seeing teeth in a dream meant the members of the family and it is more or less clear which tooth stands for which member and hence seeing that a tooth is fallen foretells the death of that member etc.

Although a dream is a mirror of future as a decreed command of God, but in a similar manner in which a person can bypass the decreed order of an despot[20] ruler and change his/her bad fortune into a good one, there is also some degree of freedom for an opposite metonymical interpretation of what is seen in a dream. This free space for metonymical interpretation lets the dream expert to interpret (taʿbīr) the dream for this opposite meaning which is the art of a good skilled interpreter to enjoy all the facilities given in the elaborate set of interpretive devices in the large Islamic culture of dream for bringing a happy dream into life. Then, interpretation or taʿbīr is essentially an effort for giving birth a bad-fated dream into the real world in the form of a good-featured happy tiding. It is an art for bypassing or avoiding the bad-fated meaning ‘written’ in the decreed ‘word’ of god as the ruler (ḥākim) on our life. In this art the instant direct meaning of the dream may be bypassed by using the potential of the words for being read differently and this is perhaps one of the reasons or interpretations that the word used for interpretation in this culture is taʿbir which means ‘to pass’ as like somebody passes a bridge. Taʿbir or the declaration of ‘word’, marks the transition from destiny to ‘chance’ through the capacity of the word for metonymy. Here a moʿaber or interpreter helps or better to say ‘cares’ a dream to be correctly materialized in our world, that is, to come correctly and healthy from its origin that is the world of imperative ālam-i ʾamr into our side that is in the world of creation ālam-i khalgh in the form of happy happening or even to abort it by giving some advices to the dreamer like giving an alms (ṣadaghe) and charity. But still the main instrument in the hand of a dream expert is ḥosn-I taʿbir that is to take the dream content as a good tiding and this mostly happens by means of his expertise on the symbols and their alternative meanings in Quran and books of hadiths. The meaning of these words are mostly primal and based on its special science of hermeneutics thereof the meaning of a word is changeable. The interpreter modifies the meaning of a word -and accordingly a decreed event in future- by revolting and deferring its original referential point as in the case of Maʾmoun’s dream[21] [22] . All these are also not far from the concept of protected board (louḥ-i maḥfouz) and its embedded paradoxical options for changeability known in Islamic philosophy as louḥ-i maḥv wa Iṯbāt or the board of elimination and confirmation which again is based on some verses of Quran: “Allah eliminates what He wills or confirms, and with Him is the Mother of the Book.” (13:39) (see for the relation between these boards: Jafari, 2001)

The language of dreams in a Persianate society

Alle Orakel reden die Sprache in der du fragst.

—Ernst Bertram

The dependence of dreams to something imperatively fore-written in ālam-i ʾamr also justifies their stereotypical nature and unchanging structure in Islamic tradition of dreams because they are just some shadowy manifestation of the unchangeable Godly tradition (sonat-i ʾIlāhi). But dreams in a Persianate context have particularly one more feature than Islamic dreams as a whole that helps them to follow the same grammar of the fore-written dreams in their folklore and accordingly fore-written literature.

A special feature of Persianate societies that the anthropologist Jean Lecref has again related it to a less explicative term of ‘Islamic civilization’ as a whole:

Consultation of sources in folklore seems to do little beyond confirming, in more or less original forms, the important role dreams played in general popular representation and in Islamic civilization in particular (Lecref: 365).

This extra feature is but due to the general forbiddance that exists as a normative against the popular representation of individuality in Persianate societies (and not necessarily in the Islamic civilizations). This camouflage of ego is related to the economic and technical determinism of ghanāt and the culture aroused from the watering system reviewed in the first chapter of my dissertation. This determinism has constructed the society in the form of a highly bipolar but unilateral relation between the king and his subjects in a long course of the history.

We might look at these ‘ folkloric original forms’ in pre-Islamic narratives and to tie this culture of dreams which Lecref has considered them as ‘ Islamic’ to its original non-Islamic and pre-Islamic origin.

In the dissertation ‘The Book of Ascension ‘ (miʿrāj nāme) will be reviewed as an example of these ‘original forms’ and its relation with the ‘popular dreams’ would be examined. In this review it would be revealed that in all different Islamic and pre-Islamic forms of miʿrāj nāme we are dealing with texts that were copying one another. After a full review of the pre-Islamic religious books, their influence on what is called today as the Islamic dream culture would become clear. ‘The book of Ascension’ is a written text on the most important night journey in Islam. Then, the study of this book would serve as example to show that in every early written work on the Muslim tradition of interpretation there are aspects that are also copied from each other. This conclusion is supported by “the nature of the parallels between the different texts, which are in most cases so specific that it is impossible to imagine them not to result from textual interdependence.” (Lambreaux: 104). All the dreams that are gathered here from the Kurdish popular culture in the form of interviews in the appendixes are just a kind of affirmative reply to those narrative forms that one may discover in Kurdish hagiographies and religious books that this book has confined its scope on just one of them that is ‘The Book of Ascension’. The writers of these books were first and foremost conservators of an inherited pre-Islamic tradition which were survived both in Zoroastrian religious books and believes rooted in the region and oral culture. These writers liked to fill the Islamic books with things that they already knew.

All these regional details do not contradict the claim of I. R. Edgar who writes: “Islam is the largest night dream culture in the world today” (Edgar: 1).Then, what is special with this work other than its historical hagiographical survey in pursuance of the non-Islamic origins of this culture? Where is its anthropological accent?

Before answering these questions it would be helpful to make a short review on the way that many Orient scholars have tried to classify the huge amount of dream material in Muslim societies and narratives to increase its manageability. A full review of their works would take a dozen of pages then, it suffices to remind one of the most fundamental classifications done by Gustave Edmund von Grunebaum, the Austrian historian and Arabist. Other forms of classification are more or less the same[23]. Grunebaum classifies the dreams in classical Islam in the following five distinct categories:

The dreamers receives personal messages.

The dream constitutes a private prophecy.

Dreams elucidate theological doctrine.

The dream bears on politics.

The dream is used as a tool of political prophecy. (Grunebaum: 11-21)

This kind of classification reveals for example that there might be utilitarian purpose behind a dream but it is not possible to decide if there is a utilitarian purpose behind a dream from its manifest content, this categorical approach also says nothing about the structural form of dream narratives. For example in the famous dream of Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavi in which his illness was cured through a dream in which he drank a bowl of water from the hands of Ali, the first Imam of Shiites (See Pahlavi:50-51), it is impossible to decide just on the basis of its content, to which category above it belongs. It pretty fits in all five categories[24].

Moreover and most importantly , this kind of classification do not tell so much about the social class of the dreamer. It is categorized by the function of the dream. Although this function is not apart from the intention of the dreamer but this kind of categorization is unable to tell about the real intention of the dreamer as a social agent. Although to know and explain about the real intentions behind what the agents say or do is the main duty of an anthropologist but in a Persianate context and in concern with the dream narratives, the true intention is not recognizable neither from the manifest form of the dream nor through a psychoanalysis of the latent content of the dreams because they all, more and less, obey the same grammar and ‘rule of tongue’, to say, they are ‘empty’. This is perhaps the reason that the scholars who have worked on the dream culture in the Islamic world, do not sort them through their structural forms of narrative. These narratives are more or less the same, especially the religious dreams narrated by a normal ‘subject’ are mostly casted in the same synopsis of which an ‘old wise man’ appears and ‘gives’ the one who has dreamt him, something like a bowl of water or else that symbolizes the fulfillment of his/her wish. We have terminologically named this ‘old wise man’ as bābā and this given ‘thing ‘ as ‘Water’ or ‘āb’. Then ‘Bābā āb dād’ or ‘Papa Gives Water’ appears to be the most popular formula of religious dreams. This formula is a theoretical tool to show that regardless of the superficial differences that dreams have, they are structurally the same. It is through this undifferentiated and hence recognizable structure of popular dreams that they are able to become circulated and found publicity (or at least try their chance for finding publicity). For those who are in the substratum of the society’s pyramid, the only way to find an ear for hearing their collective repressed wishes is to see or make ready-made dreams with common empty narrativty. The more a dream deviates from the pre-known structures, the more they reveal the individuality of their dreamers and hence they would not be able to circulate. This is analogous to ‘private money’ that is failed to circulate because money, per definition, should be collective in the sense of its recognizablity for every one of its value. This homogeneity of popular religious dreams have pushed them aside from an anthropological structural analysis. But this should not gloss over the importance and necessity of such an analysis and quite on its contrary it is exactly what an anthropologist should risk to do. Such an analysis is on the level of “thick description[25]”.

It is like the interpretative effort of a “twitch”. A twitch of the eyebrow for itself is a twitch but to know if it was a communicative intent behind a twitch or a mere physiological reaction we need to make a “thick description” (cf. Armittage: 98). The twitch by itself is then ‘empty’. In the same manner the interpretation of the intention behind the narration of a dream, in its popular form and in a Kurdish context, is similar to the interpretation of the “empty language” of a twitch (reconsidering all the notions already discussed in the first part according to the Lacanian term of “empty language”) because the intention of the dream’s narrator is totally different from its interpretation and it is usually impossible to reach from one to the other. Its interpretation is already there, reserved in their manual of dreams i.e. in the dream book of Ibn-i Sirin but this option that its narrator has fundamentally faked it is also possible because some social gains and benefits are thinkable for narrating a fake dream. For example seeing the prophet in a dream signals the virtue of its dreamer and hence brings his status up in the eyes of the other as it is believed through a reliable hadith from the Prophet who said “whoever sees me in a dream will see me in his wakefulness.” [26]

But this hadith has nothing to do with the made up dreams. It is also impossible to decide from the narrational structure of these dreams for their authenticity as all of them are alike, following the stereotype of a formal empty description. For example in most of them the prophet is seen in the form of light and after that the dreamers woke up of the excitement of knowing that this light is Mohammad.

By considering this empty language, one discovers that some stereotypical synopsis and structures of narrativity is that thread that sews and links vertically all the five different categories listed above recognized by Grunebaum and this is why that it is nearly impossible to guess from the content of a dream alone to which category it belongs.

The anthropological effort of this work lies in the structural analysis of this multifaceted valorized culture of dreams. This effort is a reductive one in which all of the dream narratives will be sublimate into its most elementary components to achieve some simple formulas such as ‘Bābā āb dād’. Without using this kind of structural and meanwhile reductive formulation to reach the main grammars working behind the dreams, the logic of the dreams would be lost in the ambiguity of abundant rich forms that dream stories could ever take through their different facial elements. For example in the mentioned formula of ‘Bābā āb dād’ the term āb is used as a register that potentially could be filled with potentially infinite elements as like as money, jewel, news, present, consult, helping…or water. It is premised here that this reductive approach would finally lead to the ontological origin of these dreams which in turn, makes the description of their ontic behavior easier.

To differentiate between the structural forms of the dreams was that traumatic abyss that this work is endeavored to work on it, at least at its beginning, it had the pretension to differentiate and sort the dreams according to their structure, truth value, functionality and so on..

Here we should consider not only the terms but also the relationship between the terms of a dream story-line. Then this approach falls pretty well in the field of ‘Structural Anthropology’. The other reason that makes this approach structuralistic is that for a structural analysis of a culture it is needed to allocate its elements in a some kind of ‘signification table’, that is to sort out the “structures of signification” in that culture to make it meaningful or decodable. Then working on the dreams is a readymade ethnographical work in this sense that every culture (of dream) as a symbolic construction, develops its own dream-books which are in fact and before everything else, some look up tables of significations which are usually constructed like a dictionary of literary symbols: ‘this’ stands for ‘that’ and ‘that’ stands for..and so on. This is somehow like what Lacan refers to as the chain of signifiers by proposing a dictionary as an example with this difference that the chain of signifiers in a dream-book has no ‘slippage’ as it has in a dictionary (each word stands for many meanings and every meaning of a word (as signifier) covers just some parts of its ultimate ‘signified’ and so on..) (cf. Seminar III, p.32). Instead, the relation between a symbol in an ‘Islamic dream’ and its meaning is rather indexical, fixed and localized. Although nothing is absolute and there is a big similarity between Islamic and Western theories of dream, and what is referred here -as the potential of the words and signs for metonymical interpretation in Iranian culture and languages- is perhaps something universal, but this feature is over-weighted in this cultural context. The capacity for metonymical interpretation rests on the inner feature of every language. What is represented here as a hint, is the higher capacity and capability of Persianate languages for metonymical occurrences as a long function of totalitarian autonomous states.

Every reader of this book has perhaps read about the ‘Oriental despotism’ or similar out-dated concepts of 19th imperialism, but it may interesting to take a look on the effect of this despotism on language as their objective collective form of unconsciousness[27] especially in those domains that it works metonymic. In fact without metonymy (as a capability for seeing ‘this’ as ‘that’) there would be no ambiguity and unconscious.

We already know by the study of “Religious Totalism and Civil Liberties” in western societies (Lifton, 1987) that the first characteristic process of ideological despotism is “milieu control” which is essentially the control of communication and if the control is extremely intense, it becomes an internalized control: an attempt to manage an individual’s inner communication. A dream is the best example for an inner communication.

Now by considering an Oriental community in which a despotic king as the symbolic father impediments and conditions the reach of his people to their desires -and also by considering the synergic effect of the blend of religion into politics in this person that bestows him a godly aura in an indexical relation with the almighty god (i.e. in an Islamic-Iranian context the king is considered as the shadow of Allah: zil-ollah)- the people recognize him as their common objection and obstacle for their desires[28].

This collective and meanwhile psychological stance of the people against their king as the one who shadows on their lives and -both physically and mentally- represses their desires is describable with ‘Ressentiment’ in the words of Max Scheler which for him, is itself a repressed form of revenge:

Revenge tends to be transformed into Ressentiment the more it is directed against lasting situations which are felt to be ‘injurious’ but beyond one’s control – in other words, the more the injury is experienced as a destiny… Through its very origin, Ressentiment is therefore chiefly confined to those who serve and are dominated at the moment, who fruitlessly resent the sting of authority. (Scheler: 45 via Kospit: 120)

This common and grim sense of Ressintiment, gives to the so-called ‘inner communication’ of the subjects – with whatever ironic meanings that it may have- a strong collective dimension so that they share their common desires -and meanwhile their inner-control for avoiding these desires- in the words and the language that they use in the daytime. Dream as field of inner communication becomes a lot of known forms of cliché’s or emptiness because the ‘subjects’ are undifferentiated and even in respect to that common thing that they dream about.

The difference between a king’s dream as an integrated free person and the dreams of unintegrated persons who dream in the automated way of routine doing of every other things is the difference between a True and False Selves (cf. Winnicott: 148). Notwithstanding of the true intention of the False Self[29], this False Self “is represented by the whole organization of the polite and mannered social attitude” (ibid: 142-143) can become all too compliant to environmental demands and all too imitative of others and all too ready to be exploited by them (ibid: 146-147). The dream narrative of the subjects (in spite of the king’s) eschews spontaneity, presenting an average compliant False Self, reifying it into a ready-made dummy as empty as everyday’s social manners and routines.

This emptiness has a common and wide range for occurrence and appliance in language as the common medium for communication from a word till a full narrative. Then, this fact that makes the realization of the real intention of a dream narrator for narrating a dream impossible, has the common phenomenal ground with the emptiness of speeches used in social manners (tʿārofāt) and the formalities used in the official administrative bureaucratic correspondencies and accordingly in the ambiguity of bipolar meanings in the primal words[30] [31].

Before going further and describing the social aspects of ‘primal words’ it is necessary to describe why this much emphasize on a linguistic subject such as ‘primal words’ is ever necessary in a book that is supposed to be mainly focused on the dream culture among the Sufis.

Firstly and particularly, the abundance of primal words In the Sufis’ literature is one of the main features of Sufis’ language and Iranian languages in general because it has developed mainly under the shadow of Sufis’ culture or better to say counter-culture. On the other hand, the language has the primal primacy for the intelligibility from a dream. Notwithstanding this famous quote of Lacan which says “unconsciousness is structured like a language” there is even a more basic tread that ties the dream to the language and it is the language in which a dream is narrated: “The symbolic language of a dream should be translated into that of waking thought. Thus symbolism is a second and independent factor in the distortion of dreams, alongside of the dream-censorship” (Freud, 1916: 168)

Then the dream symbolism is a allocation table of signs and signifiers that works in subordination to language as a the major system of signification and also the main source of distortion.

Secondly, the study of primal words –condensation of two contraries in one word- is a general study of dreams when we recall of ‘condensation’ as one of the main treats of the dream-work for taming two insurmountable opposites (i.e. id and superego) in one composite. Freud likewise argues that “among the most surprising findings is the way in which the dream-work treats contraries that occur in the latent dream…Conformities in the latent material are replaced by condensations in the manifest dream. Well, contraries are treated in the same way as conformities, and there is a special preference for expressing them by the same manifest element.” (Freud, 1916: 178). A primal word is a collective dream-work. (See also the after-thoughts of this section.)

This correlative relation between the primal words and dream-work is more conspicuous among the Sufis because all the Sufis symbolism, argot language and literature is essentially based on their invention -as well as innovative use- of a set of primal words. Every word or symbol used in Sufism has an opposite value in the normal and practical life of a Muslim if he/she ever minds to remain religious (moteshareʿ)while a Sufi utilizes this linguistic privilege to talk deliberately about wine, woman, sexuality etc.. A deep understanding of this feature of Sufis’ language is the key-point for understanding the Iranian languages, poetry and dreams because the Iranian literature is scarcely considerable without the immense influence of Sufis through their inventions of ‘primal words’.

Primal words and the pyramid of the society

Dishab ṣedāyi tishe nayāmad ze Bistoun

Gouyā be khābi Shirīn Farhād rafte bāshad

The clack of chip-axe was not heard from (the mountain of ) Bistoun last night

Perhaps Farhād has went to a deep sweet sleep[32].

Freud has used a line from Aeneid as an epigraph for The Interpretation of Dreams (1900): “Flectere si nequeo superos, Acheronto movebo”: “ If I cannot bend the higher powers, I shall stir up Hell.“ This epigraph is used by Freud to allude to the relation between a dream and wish-fulfillment. This wish -at least in the extent of this epigraph- is a political wish that is a wish for coming up in the social pyramid as a superior. It is helpful to keep in mind that even the inferno and heaven, in the divine comedy of Dante, are in the form of pyramids. Freud’s unconscious, which he equates with the Acheron, shares certain crucial features with underworld but underworld could meanwhile be interpreted politically to share features with the people from a lower social strata and emarginated people. This is the social aspect of underworld and the transparent (and meanwile subliminal camouflaged) objective aspect of unconsciousness in contribution with a more general and universal theory of dream.

Boticelli’s depiction of Dante’s Inferno

Most of the things that we learn from the ‘return to Freud[33]’ project of Lacan is to understand that the ‘symbolic order’ is that social world of linguistic communication through which the society dictates its rules in us that is in our unconsciousness or to put it in his own famous formulation: “the unconsciousness is structured like a language”. Unconsciousness speaks (ce parle) in us and mirrors the same structure of symbolic order- or Levi Strauss’s ‘order of culture’- by mediation of language. It articulates our desires in the interstices of what is permitted by the big Other. In other words, the structure off society (its pyramid) and unconsciousness are in conformity with each other.

Although Freud was not familiar with the new structuralists approach into language but in ‘return to Freud’ we understand that Freud’s ideas of “slips of the tongue,” jokes, and the interpretation of dreams, all emphasize the agency of language in the constitution of ‘subject’ and the topology of mind. Especially and in his use of the Aeneid’s expression as the epigraph of his work, he reveals his attention toward the structural body of unconsciousness and moreover the mirror-like conformity between the pyramid of the society and this structure as the subjective reflection of this pyramid on mind. This reflection is nothing more than the ‘symbolic order’ which mediates the relation between the subject and the big Other by means of language. In other words, the failure for access to conscious mental life has found its expression -according to a Freudian western theory of dreams- in unconsciousness that is in the compromise formation of dreams, slip of tongues , jokes and symptoms. In the collective reflection of this theory, the stress is again on those recognizable moments that the unconscious breaks through the conscious thought but not of a individual subject but in the conscious thought of all subjects and people, that is in the ‘ words’. In other words -and in the domain of appliance of these theories for a hydraulic state- this expressive function of language remains no more subjective, just in the same way that the pyramid of the society is no more an abstract schema and is overtly visible in the water pipes of watering system. In the first chapter 1-1: BĀBĀ (pp.93-130) of my dissertation and in our review of the watering system of Sanandaj, it was generally discussed that how in a Karizian civilization or hydraulic states in these Persianate societies the aqueducts sketch the fixed reified lines of the societies pyramid. In this real body of pyramid, the water flows from the pools of the water-lords through a network of conduits into the houses of people of a lower status and so forth… Then these water conduits are some physical traces who schematize the social pyramid in ‘flesh’ so that the social class of everyone is observable by a simple look into the way that he is watered in this watering system. Channels of Qhanāt are both a ‘model for’ and a ’model of’ the society. The social class pyramid is hence not an abstract schema anymore but something real, concrete and visible in the pipes of water in which the domains of ‘real’ and ‘symbolic’ are perfectly coincided with each other.

As the symbolic order and along to it, the structure of unconscious and language are all due to the reciprocal reflection of the social pyramid in the ‘subject’, the overt realization of this symbolic order in the real body of water pipes, calls for a similar objective realization of unconsciousness in the language. This objective realization of suppressed desires of the subject is reflected in every aspect of Iranian languages including Kurdish: in the built-in facilities of these languages for talking ironic or even to say lies[34], in the empty language of everyday routines, hidden intention of the narrator of a narrative, dream story-lines and most exemplary in the ‘primal words’.

As all of these different genres are of the same nature, explaining the ‘primal words’ may reveal many facts about the dream culture. The reason for this focus is self-evident because it is more simple to analyze a simple word than a full narrative.

To see the importance of this analysis, it is useful to realize that a dream story as a whole could behave like a primal word, that is it could be understood as its far opposite. As Iain R. Edgar has also noted in his book: ” In certain dreams, inversion takes place and a dream symbol must be assigned a meaning opposite of its apparent meaning” (Edgar: 110. On the next few pages he has denoted -as a difference between a “Western Psychological Theories of the Night Dream” and an Islamic theory- that: “ In Islamic theory the manifest dream content can be the same as the latent one” (Edgar: 113). This ‘primal’ feature of narratives in the Persianate societies and their capability for ‘double signification’ finds its root in the hermeneutic nature of Oriental way of discourse mostly innovated by Sufis especially by innovating a new brand of ‘primal words’ in which for example a word like mey or āb stands for heavenly knowledge and intoxication but simultaneously signals for its opposite that is the worldly wine and drinks or the word sāghi (the one who serves wine)who stands for an ‘old wise man’ but is depicted in the Sufis’ literature as a young beautiful woman[35]. This trait is not restricted to the ‘primal words’ and in fact the same logic- that rules over the ‘primal words’ in Arabic, Kurdish, Persian and especially in Sufis literature- also rules on the dream books . As our focus is on the Kurdish people and the book of Ibn-i Sirin is the most favored and popular dream book in the Kurdish culture, here are some examples of this logic in which two opposite things share the same interpretation:

To see heaven (jannah) mostly predestinates its dreamer as one who enters the heaven after death but seeing the hell (jahīm) could be interpreted either as hell or heaven that is as its far opposite (cf. Ibn-i Sirin: 125-126). Water and fire as an insurmountable pair have also the same interpretation, seeing water and fire both stands for a king (Ibn-i Sirin: 375). Seeing a desert without water and also a land without food (ghaḥṭī) both stands for a fertile time and richness (Ibn-i Sirin: 386-387). The examples of this kind are many. The complexity of understanding the logic working behind the dream books and dream manuals in an Islamic culture lies in what Freud has once named ‘assonance’ and ‘similarity of the words’ (Freud, 1900: 72). The meaning of a symbol seen in a dream is more complex to be deducted from its superficial meaning and a dream is a fantastic ‘nominal’ riddle which is supposed to have actual consequences in appropriation to the way that is interpreted. This fact that a dream is a riddle is seemed to be universal Every dream is a riddle that should be solved. This makes at least one element in the Oedipus complex universal: the sphinx, as the one who asks riddles. In contrast to sphinx, Oedipus is the prototype of a dream interpreter who is tragically confronted the consequences of his knowledge. One main difference that one can delineate as an early conclusion is that the answer of this riddle in Occidental modern psychology as the established form of dream interpretation is an striving wiliness for confronting a terrifying truth about the dreamer (a terrifying event in the past or childhood, a primordial crime of patricide and so on..) and not a striving willness for confronting the events in future. Hence a dream in modern psychology is rather a mirror that tells us about the dreamer’s psychological situation, where in Oriental the science of dreams (ʿIlm ol-royā), a dream is a riddle that should be solved through the primordial pact with the ‘name of Father’, through this pact, the interpreter of a the dream is also a fore-seer and dream functions as a mirror for seeing the future.

This pact is the language or the science of names or ʿilm ol-asmāʾ, a science that is the point of privilege of human being (ādam) in compare to the other creatures of the god in an Islamic system of philosophy. A good interpreter is the one who masters this science and through this science helps the dreamer to avoid the consequences of a primordial crime or sin through a different read of the dream that potentially entails opposite interpretations and meanings[36]. Hence a dream in the Oriental science of dreams (ʿIlm ol-royā) is a changeable fate and a mirror through which one can see both the spiritual stand and the destiny of the dreamer. Regardless of how complex and professional this science of dreams (ʿIlm ol-royā) could be, which is out of the scope of this book and knowledge of this writer, one thing is sure and that is the crucial role that language as a rule plays in the interpretation of what has been seen in a dream. This language for a Muslim who is familiar with the Quran (as the words of Allah or kalām ollah) is Arabic but this does not dismiss the influence and associations that the native language may put on the dream’s modality of interpretation. The close relation with verbality (kalām) and the ‘written’ (maktoub) is reflected in its best in the name attributes of Quran which is not kitāb ollah (that is the book of allah) but Kalām ol-llah or the words or sayings of Allah.

Besides, the word ‘word’ (kalame) in Arabic has preserved its oral, verbal nature: Kalām comes from takalom or speaking and accordingly Qurān should be understood as the sayings of Allah. This is also the general name that for example Ahli–ḥaqq in Kurdistan have given to their religious books: Kalām-I Ahl-i ḥaqq (In a similar way Qewl among the Yazidis??) . Studying the connectivity between maktoub, -which literally means both mandatory and written- as the law of God and the verbal and even vernacular origin of the languages in which the religious book are written is not a side track of studying the dreams. ‘Speech’ (kalām) and ‘word’ (kalame) in an Islamic context are ontologically and etymologically related to each other. One (the oral literature) is the origin of the other (written) and nonetheless today they are blended to each other: