The Loop, the Cut, and the Voice:

Lacanian Logic in the 100 Prisoners Riddle

Iraj E. Ghoochani

Before diving in, the reader is encouraged to watch Veritasium’s video “The Riddle That Seems Impossible Even If You Know the Answer” (link), which clearly introduces the 100 prisoners riddle. This logical puzzle will serve as the structural foundation for the Lacanian exploration that follows.

A Logical Prison

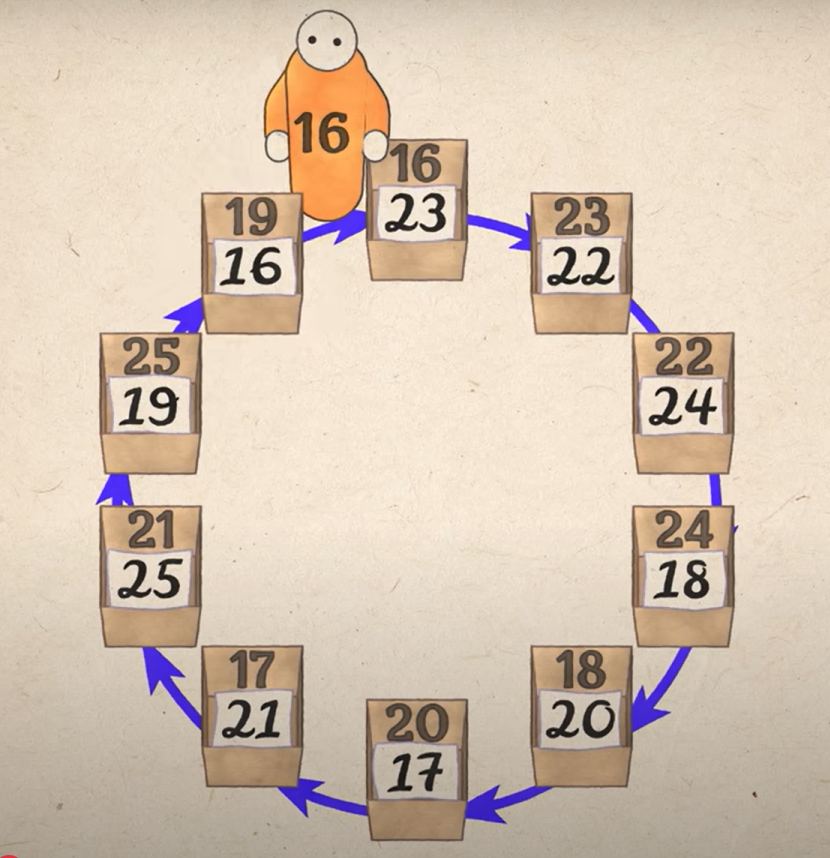

Imagine a room with 100 boxes, each labeled with a prisoner’s number. Inside each box is a slip of paper, bearing a different prisoner’s number — all placed randomly. Each prisoner may open up to 50 boxes to find the slip with their own number. If all prisoners succeed, they are freed. If even one fails, all are executed.

At first glance, this appears to be a cruel thought experiment in probability. But beneath this grim setup lies a surprising strategy — a loop-following method where each prisoner opens the box labeled with their number, then follows the number found inside to the next box, and so on, until (hopefully) they find their own slip. This method raises the odds of collective success from near zero to over 31%, entirely through a logic of structure.

![]()

Yet, this loop is a metaphor. In this essay, I argue that the 100 prisoners riddle, especially when reframed through Lacan’s lens, becomes a model of subjectivity, language, and the structural cut that produces desire. The loop (effectively a chain of signifiers) is not only a strategy; it is the symbolic order itself. The traversal is the subject’s movement, and the elusive slip of paper inside the loops is the object (a) — the structural lack that sustains the entire game of being.

The power of the prisoner strategy lies in its use of loops: each prisoner follows a deterministic path that will either close back on itself or exceed the allowed number of steps. Every box contains a number, pointing to another box, forming a closed permutation — a cycle. The condition of success is not randomness, but that no cycle is too long.

In the video explaining this riddle, the host states:

The slip and box with the same number essentially form a unit… every slip is hidden inside another box… necessarily forming loops.

This insight reveals the riddle’s deeper logic: there is no way outside the structure. Every attempt to step out leads deeper in. There are no dead ends — only chains of signifiers, each pointing to the next. This logic mirrors Lacan’s use of the induction puzzle, described in Session 14 of Seminar XIII. There, Lacan recounts a trick:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 — what’s the smallest whole number not written on the board?

The subject hesitates: is it 6? 0? None? But any answer is immediately recuperated by the structure — it is now “on the board.” The puzzle is not a game of cleverness, but a trap of language — a short-circuit that “cuts you off” and exposes the subject to the symbolic order.

Both puzzles — the prisoners’ riddle and the number induction — share a structure: a loop that always closes, but never completes meaning. In Lacan’s terms, this closure introduces the object (a) — not as a thing, but as a remainder, the trace of what is missing yet structuring. Lacan says:

It reintroduces you… into the question of language, founded, as you see, on writing, the object (a).

This object (a) is the slip the prisoner seeks, the missing number the speaker tries to name. It cannot be found directly — it is approached through misrecognition, through a loop of displacements. Every move toward it intensifies its absence. The loop thus functions as a symbolic chain, and the object (a) as the void around which that chain turns — like zero in mathematics, which is not just the start of the number line, but the condition for counting itself.

Quality from Quantity: Infinity and the Scent of the Object

The loop is not defined by its number, but by its form — and that form is potentially infinite: “Quality comes from the fact that quantity could be endless.”This a the Lacanian move: even a finite set — like 100 boxes — contains infinity, because it invokes the logic of completion, and then reveals its structure after each iteration: The prisoner never knows where their slip lies. Each traversal is a desiring movement, one that risks not returning. Is all these are not already inscribed in graph of desire? That is essentially a loop? The object (a) — the desired slip, the missing number — is imbued with the scent of infinity. It is not just absent — it is indecidable. It is zero, not as a quantity, but as a condition: the short-circuit that allows symbolic loops to function.

The Voice: Echo from the Gap

In the same session, Lacan turns toward a less obvious register: the voice. He warns:

Don’t take the voice to be simply sonority… it has absolutely nothing to do with that.

For Lacan, voice is not what is heard, but what insists — what remains after the symbolic has done its work. It is the trace of the subject in the chain of signifiers, the resonance of failure. In the prisoner riddle, there is no speaking. And yet every traversal is a structural voice — a movement through the symbolic that echoes subjectivity.

When the loop fails — when it exceeds 50 steps — the Real erupts. The structure breaks. This is the moment of the psychotic voice, which Lacan describes as a return of the sensory in the absence of symbolic containment. The loop is too long; the subject is no longer held by writing.

Castration, Writing, and the Induction of the Subject

Does this structure relate to castration, Lacan’s name for the structural cut that produces the subject? He says:

Does that mean that with this ‘it cuts you off’ we have the whole of what is at stake concerning castration? I’d say no. It’s only a question of the object (a).

He distinguishes here between castration as symbolic inscription and object (a) as its effect. The loop — whether numerical, linguistic, or logical — introduces the cut, the point of impossibility. The subject, navigating this loop, is divided, constituted by what they cannot reach. The writing in this context — numbers on boxes, slips in containers, numerals on boards — is the act of structuring, but its failure is productive. It makes the subject appear. Lacan emphasizes:

For something written to hold together, you have to pay your own way.

This is the cost of subjectivity: to traverse a structure that always threatens to exclude you, and yet is the only place you can be.

The Loop as Parable of the Subject

The 100 prisoners riddle is not a game — it is a parable of the speaking subject. The prisoner is a subject in Lacan’s sense: They begin at a misrecognized label (Imaginary). Traverse a symbolic chain (loop). Confront the structural impossibility of direct knowledge. And move toward a truth they can never fully possess — the object (a).

This is the Lacanian drama of being: Not to find the answer, but to traverse the structure. Not to speak, but to be spoken by the voice that writing leaves behind.

Not to name the missing number, but to be cut by it, and in that cut, become a subject.

Conclusion

I tried here to read 100 prisoners problem through the lens of inductive reasoning as a structure of subjectivity, and not just as logical trickery. There is a silent strategy that is collective in nature at least in the sense that if a loof is smaller than 50, each of the prisoners without any need to talk with each other are destined to be free. It is the structure itself that rules.

Lacan uses the induction puzzle in Seminar XIII not as a curiosity but as a structure of anticipation and castration — of the subject caught between the signifier and the impossible referent. In the puzzle:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 — what’s the smallest whole number not on the board?

The trap isn’t logical, it’s symbolic: anything you say becomes part of the board, part of the Symbolic Order. Meaning is always-already pre-inscribed, and the subject’s response is always captured. You’re “cut off” by the fact that your response gets immediately folded back into the structure. So this “cutting off” is the experience of the subject of castration: the subject is barred, separated from full meaning, from fullness of presence, by language.

The 100 prisoners riddle is another induction structure. Here’s how it plays out: The loop is like a proof — an inductive path. So: every prisoner becomes a subject of induction — they enter a symbolic chain, and their survival (subjectivity) depends on fidelity to structure, not randomness, not “knowing.”

A proper Lacanian idea is not to show that puzzles are clever but in that they reveal how the subject is structured in language. Es is a S=signifier, and Es spricht — it speaks — because the signifier (S) speaks before and beyond the subject; even silence is caught in this speech. It is not the subject who speaks, but language that speaks the subject. So for both the numerical puzzle (1,2,3,4,5—what’s missing?) and the 100 prisoners: The trap is not the missing piece, but the assumption that something is missing outside the symbolic: the void inside the loop. Once you speak, you’re written, and thus “cut off.” To find the object (a) is to confront the Real, not directly, but through symbolic failure. The Real is never in the “right place.” The traversal itself is a castrative cut — the subject loses the fantasy of direct access.