The Orthogonality Between “Home” and “House”:

A Linguistic and Intercultural Perspective

Iraj E. Ghoochani

A house shelters you from the world; a home reveals who you are within it.

Let us start with etymology. There is a lot that we can learn from the etymology of “house” and “home”, showing how these terms evolved to differentiate as well as represent both physical and emotional dimensions of dwelling: A house is a place to hide from others, while a home is where you find yourself among them.

House: A Place of Shelter

The word house comes from Old English hus, meaning a dwelling or shelter, rooted in the Proto-Germanic hūsan. Some scholars link it to hide, suggesting early meanings of the house as a place of protection. Over time, house extended to broader meanings, such as noble families, Zodiac signs, and institutions, transforming from a mere structure to a symbol of power and identity.[1]

Home: A Place of (Be)longing

Home derives from Old English ham, meaning a dwelling or fixed residence, with the Proto-Germanic haimaz connecting it to villages or communities. Unlike house, home represents not just a physical space but also an emotional state of comfort and belonging, rooted in the Proto-Indo-European tkei– (to settle or dwell).[2] Doesn’t this broader sense of home conveys a deep existential be-longing that transcends the physical realm?

Home vs. House

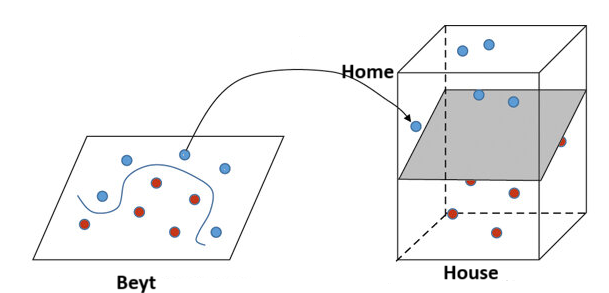

As seen above, the terms home and house represent distinct and often orthogonal concepts. A house is generally understood as a physical structure—a building made of bricks, wood, or stone, while home carries deeper significance. The former is tied to the material world, while the latter reflects attachment, warmth, and personal meaning. This distinction marks an almost Cartesian separation between the tangible and the abstract, aligning with a tendency toward metonymic differentiation, where physical and symbolic realms are kept conceptually separate.

Home/Metaphor/Desire/Paradigmatic/Emotional/Condensation

House/Metonymy/Repulsion/Syntagmatic/Physical/Transformation

However, in some languages like Arabic and Farsi, the boundary between the physical and emotional aspects of a dwelling is fluid, often intertwined. Both Arabic’s بيت (bayt) and Farsi’s خانه (khāneh) can be used interchangeably to denote both the physical building and the emotional space that constitutes home, depending on context. This flexibility points to a broader cultural and linguistic framework that does not prioritize a sharp division between the material and the symbolic.

House + i Home: A Complex Metaphor in Arabic

To understand this blending more deeply, consider the word house in Arabic, بيت (bayt), as a complex number in mathematics, composed of a real part and an imaginary part: House + i Home. In this analogy, the real (=Symbolic in Lacanian terms) part represents the tangible, material aspect—the physical building. The imaginary (=Real in Lacanian terms) part represents the cut: a sort of resonance that gives meaning to the space through a void that evades every meaning. Together, the word functions as a rotating vector within a complex plane, where both real and emotional dimensions interact dynamically inside the fluid of utterance. Then, in Arabic, the concept of bayt does not conform strictly to one axis, but rather rotates between the material and emotional domains. The word itself becomes a fluid carrier of meaning, oscillating between the physical structure and its emotional resonance.

Beyt

Here are few key concepts from Dehkhoda Dictionary on “Beyt” (بیت):[3]

- Beyt as Home:

– House of Kaaba (خانهٔ کعبه): House of God.

– House of every one.

2. Beyt as Grave:

– Also refers to burial: the duality of home as both a living space and a resting place.

3. Beyt in Poetry:

– Poetic Structure: Represents the smallest unit of a poem (Nazm نظم, lit. means order), symbolizing order and harmony, much like the threshold of a home.

The Two-Sided Door of Golestan Palace: This magnificent entrance to one of the parts of the Golestan Palace in Tehran features a beautifully tiled wall, adorned with the vigilant presence of two guards, symbolizing protection and strength. Above the door, a verse from the Quran—”إِنَّا فَتَحْنَا لَكَ فَتْحًا مُبِينًا” (Indeed, We have granted you a manifest victory)—captures the essence of this architectural marvel: The word fath (فتح) not only signifies victory in battle but also metaphorically represents the act of opening a door. Just as a victorious opening signifies new beginnings and opportunities, this door serves as a literal and symbolic threshold, welcoming those who enter into this space. In this context, the door becomes a powerful metaphor for triumph and transformation, inviting all to step through and embrace the grandeur that lies beyond. Two Sides of a Door: The door to a home, in general, serves as a boundary between the inner emotional world and the outer physical world, paralleling how a beyt connects these themes and ideas within architecture as well as in poetry.

The Two-Sided Door of Golestan Palace: This magnificent entrance to one of the parts of the Golestan Palace in Tehran features a beautifully tiled wall, adorned with the vigilant presence of two guards, symbolizing protection and strength. Above the door, a verse from the Quran—”إِنَّا فَتَحْنَا لَكَ فَتْحًا مُبِينًا” (Indeed, We have granted you a manifest victory)—captures the essence of this architectural marvel: The word fath (فتح) not only signifies victory in battle but also metaphorically represents the act of opening a door. Just as a victorious opening signifies new beginnings and opportunities, this door serves as a literal and symbolic threshold, welcoming those who enter into this space. In this context, the door becomes a powerful metaphor for triumph and transformation, inviting all to step through and embrace the grandeur that lies beyond. Two Sides of a Door: The door to a home, in general, serves as a boundary between the inner emotional world and the outer physical world, paralleling how a beyt connects these themes and ideas within architecture as well as in poetry.

The Metaphoric Axis of Oriental Languages

The fluidity between house and home in Arabic and Farsi reflects a broader cultural and linguistic tendency in these languages to rely more heavily on metaphor. Oriental languages often emphasize metaphorical meaning, stretching their lexicon across both tangible and symbolic realms simultaneously. This metaphorical richness allows concepts to carry multiple layers of meaning without the need for strict categorical distinctions.

In contrast, Western[4] languages tend to extend more along the metonymic axis, favoring precision and clarity in separating concepts. Sociocultural factors play a significant role in this divergence. The linguistic structure of Western societies, particularly influenced by industrialization and scientific rationalism, has cultivated a mode of expression that values distinction and clarity, drawing clear lines between the material and the abstract.

In Middle Eastern and Persian societies, however, language has evolved within a unified field in which power and religion share the same room and this condensation bestows its feature into language as an objective form of the dream-work.[5] The poetic traditions of Arabic and Farsi, along with a historical emphasis on oral storytelling and metaphor, have cultivated a more condensed and integrated worldview. This worldview is deeply metaphoric, where the symbolic and material frequently intertwine. The enduring legacy of despotism has shaped a language that acts as a form of collective memory: words become condensed reflections of political pressures that span generations. As kings and their subjects rise and fall, the language persists, embodying the despotic relations that constitute an essential form of existence, much like a machine that reproduces their political subjectivity. Consequently, the language exhibits qualities of condensation (Verdichtung), often leaning toward metaphor, where a single word, such as Beyt, can evoke both physical and emotional realities depending on the context.

- https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=house. ↑

- https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=home. ↑

- https://vajehyab.com/dehkhoda/%D8%A8%DB%8C%D8%AA-3?q=%D8%A8%DB%8C%D8%AA ↑

- While I recognize that this perspective may oversimplify the complexity and richness of language, it serves to illustrate the general trends observed in these linguistic structures. ↑

- In fact the large part of my dissertation is devoted to picture the relation between the dream and the word as a sort of objective dream that circulates like currencies with a special emphasis on the Persianate states. Here is a useful paragraph: “… the administrative language evacuates an empty space in which the oppositional speech is permissible. The ambiguity of this emptiness grants the language an unbelievably large room for poetical speech and unconsciousness as an empty space in which the meaning can swing between a symbolic meaning and a real intention. In other words, instead of communicating an intention, the language is provided by a built-in empty space for hiding the intentions of its speakers which makes the language ‘Real’. Accordingly, in the epilogue a set of equivocals are listed. These Janus-words are a set of oxymorons crafted and condensed in just one word which reveals the hidden dynamic of a paradox existing between two different intentions suggested by a single word. Observing these features of language will lead us to some of its built-in facilities for avoiding the punishment in political life: censor. Now, we should notice that concepts of Father, censor, language and unconsciousness are correlated ideas webbed around dream. A dream just like an equivocal word or symbol says something in its overt appearance to communicate a covert message. A dream is a visual primal word and a primal word is a verbal dream…” (Esmaeilpour Ghoochani, P. 166)

Esmaeilpour Ghoochani, Iraj (2017): Bābā Āb Dād: The phenomenology of sainthood in the culture of dreams in kurdistan with an emphasis on sufis of qāderie brotherhood. Dissertation, LMU München: Fakultät für Philosophie, Wissenschaftstheorie und Religionswissenschaft. URL: https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/21528/. ↑