Cinema is a Film

In the phenomenology of the spirit of Iranian cinema 1

Iraj E. Ghoochani

Summary

This article explores the idea that if “the spirit is a bone”, as Hegel suggested, then this principle can be extended to other domains. Using cinema as an example, it proposes that “Cinema is a Film,” but suggests that the spirit of cinema lives in an inversion with the mere film, much like the spirit with the skull. However, no assertion is intended to be proven true; rather, each pair of insurmountable concepts, such as Spirit and Bone, Word and Flesh, Voice and Image, serves as a tool for contemplating cinema. Drawing on Iranian medieval neo-Platonic philosophy, the article suggests that the materialistic world was rather like a cinema even before the invention of cinema. The author argues that following the suit of this episteme, certain filmmakers, like Aslani, create a sort of cinema that transcends the film, favoring the spirit over the bone, specifically sound over film. For these filmmakers, the voice of the film is the true projector i.e. creator of the film, with the celluloid strips serving as the bone. However, other Iranian filmmakers, such as Abbas Kiarostami, view cinema differently, seeing it as the film itself.

Cinema is a Film

سایه قد تو بر قالبم ای عیسی دم / عکس روحیست که بر عظم رمیم افتادست

The shadow of your stature falls upon my mold, O Jesus-breath / It is the reflection of a soul cast upon decaying bones.

— Hafez

Hegel once wrote that “The spirit is a bone” (Der Geist ist ein Knochen). At first glance, the statement seems strange, almost absurd. Does he mean it literally — that the human skull is the reality of the spirit? Hegel clarifies: the tangible, physical existence of the human being is indeed their skull bone. Is this statement clear? Certainly not. But from the preceding context, we deduce he means the skull specifically:

Die Wirklichkeit und Dasein des Menschen ist sein Schädelknochen

The reality and Dasein of man is his skull-bone.

Thus, spirit is the skull. But how can spirit be “lowered” to the level of a bone? The skull is a rigid, inert object; the spirit, by contrast, is alive and fluid. Hegel’s point might be that spirit, in its concrete reality, always appears in a material form — and in this case, that form is bone. Whatever Hegel’s point might be, such paradoxical pairings — spirit and bone, word and flesh, voice and image — can serve as conceptual tools. They allow us to think about other domains, such as cinema, in the same dialectical way. Then, if we extend Hegel’s principle, we might say: “Cinema is a film.” Here, “film” is the bone — the physical medium of celluloid or digital recording — and “cinema” is the spirit that flows through it: movie.

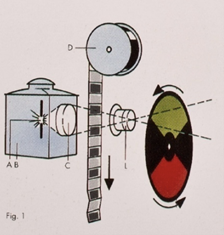

Cinematic Exorcism The film projector as exorcist: Celluloid = possessed body (light trapped in emulsion)

Projector’s beam = the rite that screams “Name yourself!”, forcing light to confess its spectral nature

Celluloid is the trembling membrane where light becomes ghost. Here in this essay, “film” refers not to stories or screens, but to cinema’s physical body—the quivering strip of celluloid that 1- Intercepts light (like a wound receiving a blade) 2-Transubstantiates it through silver and gelatin (a chemical reaction) and finally 3-Exhales as projection (the resurrection of arrested light)

Traditional metaphysics treats bone as spirit’s antithesis; Hegel collapses them. The exercise of spirit becomes synonymous with the cultivation of the skull—identical acts. Representation is looped back onto demonstration; reflection onto projection.

Yet the essential point always stands outside language, for words exist in a perpetual strike, juxtaposing themselves against their own opposites. This strike is the serious thinker’s playground—a chance to climb the cord stitching heaven to earth , neither falling nor even moving, since “up” is but the inverted image of “down” As the verse says:

مشغول بود فکر به ایمان و کافری / ایمان و کفر و شبهه و تعطیل عکس توست

The mind agonizes over faith and heresy / Yet faith, heresy, doubt, and even their suspension are but your projection/reflection.

“Spirit is a bone”—our thinker can never escape this phrase. He is condemned to stare it in the eye for eternity, seeking an answer to his own being-or-nonbeing, suspended as he is between spirit and bone.

Cinema as Film: A Kiarostamian Extension on Hegelian Axiom

If “spirit is bone,” this axiom extends to all domains. For instance: “Cinema is film.” Just as the spirit finds nothing more like itself than the skull (its earthly throne). Now, like Hegel’s proposition, this statement isn’t meant to be verified, but to provoke thought about cinema’s nature. Where Hegel’s thinker is busy with his axiom, the filmmaker—here, Kiarostami—is defined by their stance toward “cinema is film.” His famous dictum inverts the terms: “Film is nothing but a lie to get closer to the truth.” Just as the spirit discovers itself only through its inversive hollow—skull as its negative cast—so too does cinema confront its essence in the celluloid strip.

Some Iranian filmmakers—most notably Mohammadreza Aslani—represent a counterpoint to Kiarostami’s approach. Rooted in Iranian medieval Neo-Platonic philosophy, where the visible world consists merely of shadowy projections of essential ideas, these filmmakers view the voice (the Word) as the true creative source—the projector of meaning—while the images trapped in the “bone-yard” of celluloid.

Abbas Kiarostami operates from the opposite premise. For him, cinema resides in the film itself—the visual, tangible artifact. This fundamental opposition frames a crucial duality in Iranian cinema: to what extent does it privilege the disembodied voice (that spectral narrator hovering beyond the frame), and to what extent does it commit to the physical filmstrip as its own subject?

For Aslani, the voice is not simply a soundtrack layered onto images; it is the generative force of the film. The images, captured on celluloid or digital media, are secondary — the “bone” that supports the life of the work but does not itself contain the soul. This idea resonates with the mystical belief that sound can reveal truths hidden from the eye. In this model, the viewer’s relationship to a film is shaped by listening as much as by seeing. The sound can direct, even command, the audience’s imagination, while the image remains a supporting frame. The true cinema, in this sense, happens in the ear.

Kiarostami’s approach reverses this hierarchy. For him, the image is cinema; it does not require an unseen “voice” to validate it. His films often minimize non-diegetic sound and let visual composition carry the meaning. This writer suggests that these two approaches reflect deeper philosophical tendencies in Iranian thought: one that privileges the unseen and immaterial as the source of meaning, and one that accepts the tangible, visible work as complete in itself.

This contrast also invites the question: when we speak of “cinema” as something greater than the film, are we invoking a kind of spiritual metaphysics — or are we simply romanticizing what is, in essence, a material art form? This pervasive emphasis on film’s “fakeness” ironically proves its hyperreality in Iranian consciousness. I try to explain: In Persian, there are expressions like “It’s all film” (hame-ash film ast) or “Don’t act like you’re in a film” (film bazi nakon). These phrases are often used in daily conversation to mean “It’s fake” or “Stop pretending.” They draw a sharp line between what is considered genuine reality and what is regarded as staged performance: “being in a film” implies a lack of authenticity. Unlike Western traditions that prize cinematic realism as truth, Persian vernacular treats “film” as synonymous with fabrication—a layer of pretense over reality. Kiarostami’s genius was to embrace this stigma: his street scenes (Tehran’s inherent drama) risk being dismissed as “just film” (contrived), while Aslani-style transcendentalists seek the unseen voice behind the image. The tension persists: is cinema the bone (filmstrip as literal artifact) or the spirit (that which shatters it)?

The tension between “film as truth” and “film as pretense” runs through Iranian culture and, by extension, Iranian cinema. It informs both how films are made and how they are received.

Why else would: Persian “aks” (عکس, photograph) etymologically reveals photography’s inverted-image mechanism more precisely than European “photo”: Iranians intuitively grasp cinema’s magic before its machinery.

Spirit Reveals Itself Superior to Bone

In the phenomenology of the Persian spirit, death literally constitutes a Hegelian Aufhebung (from Auf + Hebung, “to lift up”): The dialectical process where bone is both negated and elevated into spirit.

The Homa bird, whose shadow bestows kingship in legend, is in reality the bone-eating Gypaetus barbatus (bearded vulture) that carries bones aloft only to drop them. Yet in the Iranian order of things, this bird solely ascends with bones to the realm of spirit.

The obvious fact—that the vulture lifts bones to shatter them—is censored. This occurs because myth’s purpose isn’t to reconcile social order with cosmic order, but only to simulate their harmony. Iranian myth operates as ideological suture—concealing the materialist violence (bone-shattering) beneath the symbolic spiritual transcendence.The Homa is thus Iran’s mythic machine for transubstantiating bone into spirit.

Now there is a Forbidden Inverse: Spirit’s reduction to bone is demonic—like trading love for lust, as Bidil-i Dehlavi warns:

آن را ﮐﻪ ﻋﺸﻖ از ھﻮس ھﺮزه واﺧﺮﯾﺪ/ ﺑﺮد از ﺳﮓ اﺳﺘﺨﻮان و ﺑﻪ ﭘﯿﺶ ھﻤﺎ ﮔﺬاﺷﺖ

He whom Love has plucked from the rubble of base desire

Takes the bone from the dog and lays it before the Homa.

While Hegel’s system maintains a bidirectional spirit-bone dialectic, Persian belief enforces a unidirectional ascent: Iranian cosmology allows only Aufhebung (sublation), not materialist reduction. Bones must ascend; their return is foreclosed. Thus, life in the lower world becomes a dog’s existence in a bone-yard. This symbolic is perpetually sweetened through language that censors the bone’s material return, enforcing one-sided transcendence.

Henry Corbin (Cyclical Time and Ismaili Gnosis) shows how the Persian psyche endures 9,000 years of demonic shadow-rule, where only the Homa’s shadow—the Farr-e Homayoun (King’s Divine Glory)—can save. The King’s shadow, unlike Ahriman’s, brings prosperity—a concept Islamized as Zillullah (Shadow of God). This is the Persian kingship theology: The Shah’s shadow recreates the primal homeland (cf. Rumi: من مرغ لاهوتی بدم دیدی که ناسوتی شدم “I was a Lahuti bird! Alas, Now I am Nasuti!”).

“Similis similibus curantor” (Like cures like) applies here: The Water of Life (light) hides in darkness. True light in this illusory world must be the darkest shadow. This is a Gnostic inversion: In a world of negative inversions, salvation requires embracing the paradox (e.g., poison as antidote). As the verse says:

زاﻧﮑﻪ زﻟﻔﺶ ﮐﮋدﻣﺴﺖ و ھﺮﮐﺮا ﮐﮋدم ﮔﺰﯾﺪ / ﻣﺮھﻢ آن زﺧﻢ را ﮐﮋدم ﻧﮫﺪ ﮐﮋدم ﻓﺴﺎی

His twisted locks are scorpions / Yet only a scorpion can heal a scorpion’s sting.

Thus, the divine Farr (glory) is none other than the King’s shadow. Iran itself is this shadow—the homeland where Persians dwell in symbolic protection.

The Optics of Power: All of Iran is a Cinema-House

Khayyam’s verse illuminates our condition:

فانوس خیال از او مثالی دانیم |

| این چرخ فلک که ما در او حیرانیم |

ما چون صوریم کاندر او حیرانیم |

| خورشید چراغ دان و عالم فانوس |

take it as a lantern of imagination—

This celestial wheel that leaves us bewildered within it.

We are but images, lost in its mystery—

Know the sun as the lamp, and the world as the lantern.

Divine Optics of Power: The Hierarchical Gaze at Behistun: The monumental Behistun relief depicts King Darius I asserting his divine mandate by subduing rebellious figures: The usurper Gaumāta lies prostrate beneath the conqueror’s foot Skunkha, the Scythian rebel (added later, disrupting the original inscriptions). A powerful fusion of art and political propaganda from 522-486 BC. The Behistun relief’s composition follows a sacred visual hierarchy mirroring Zoroastrian cosmology: The Faravahar (divine glory) radiates downward. Darius stands aligned with the Faravahar as a Royal Conduit, his raised hand catching its authority. His size (largest figure) and central position mark him as divine energy’s earthly vessel. The chained rebels diminish in scale along a downward diagonal. Gaumāta’s prostrate form receives Darius’ foot like lightning grounding divine wrath. Skunkha’s late addition breaks the pattern. The relief functions as a spiritual circuit: Divine light (Faravahar) → King (conductor) → Rebels (ground). Each figure’s size and position mathematically encodes their metaphysical status. Like Persepolis’ ritual: On Nowruz, the just king’s face remains unseen as sunlight emerges behind his throne—subjects mesmerized by this anti-light. Source: The first symposium of visual-anthropology, Tehran University, 2007 ©

Another recurring figure is the (shadow of the) king — a ruler whose power exists in a mirrored, reflected form. This symbol ties directly to cinema: the image projected on the screen is like a shadow, a visible but insubstantial authority. The “real” source lies elsewhere, behind the projection. The Shah is a mirror reflecting the divine light’s negative downward to his subjects—each receiving their allotted Kismet. Negative is used here as a photographic metaphor for how kingship inverts celestial light into earthly shadows. Kismet (قسمت): From Arabic qismah also means both “fate” and “portion”—like an actor’s pre-written role.

This aesthetic of acceptance transforms denial into grace. Consider the Persian phrase “Na, khayr” نه خیر (“No, [but it’s for] your good”) versus German “Ja-wohl”: The Persian negation carries hidden affirmation—rejection as divine mercy, unlike Germanic literalness.

The Shah mirrors the divine light; his shadow is the inverted image of that celestial light. But what is a shadow? A virtual body obeying its true source as a Platonic-Persian synthesis: The Shah’s shadow as allegory of the Cave, but with collective redemption. By submitting to the Shah—with heart, soul, and bone—we reconnect to the spirit world.

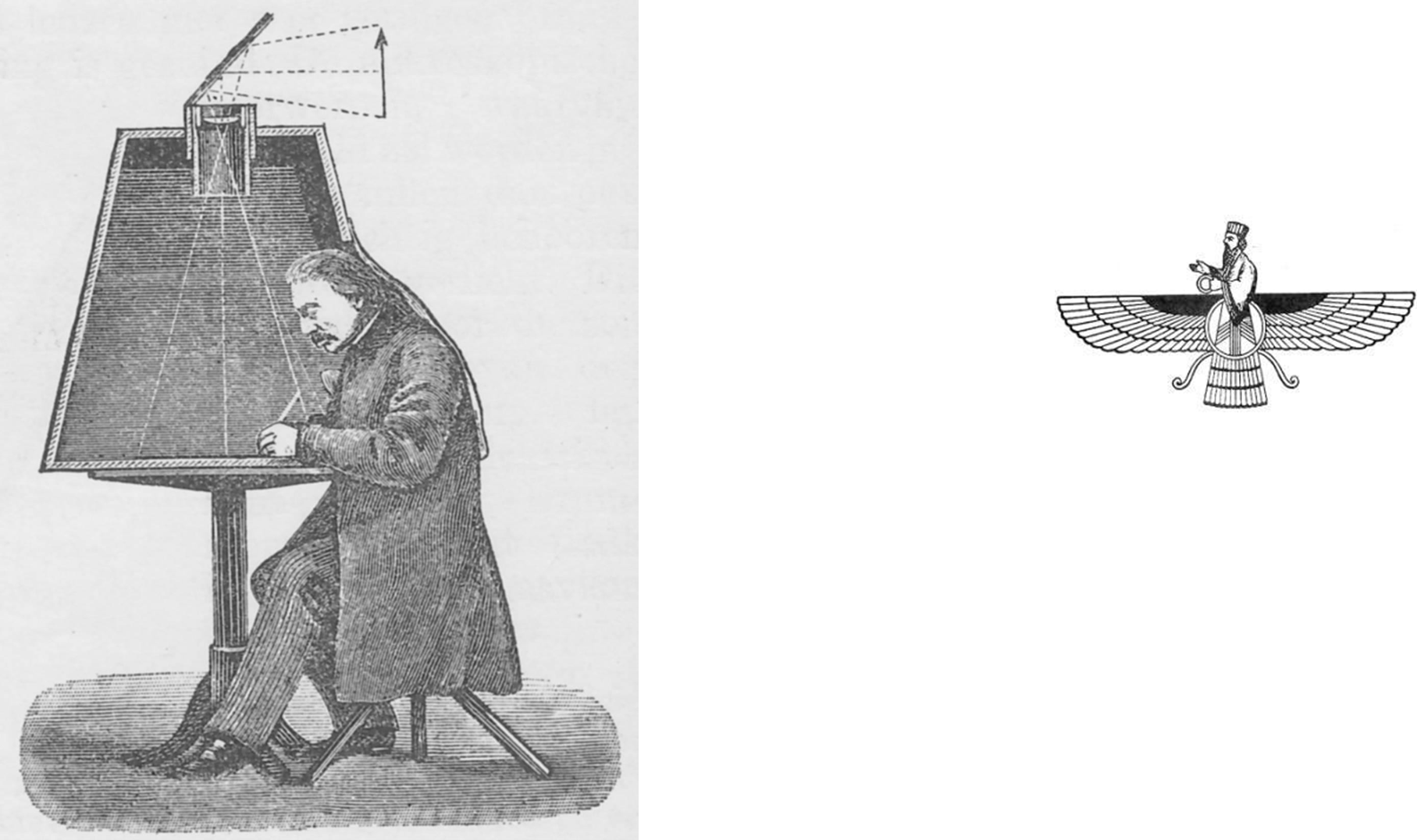

The entire Persian bureaucracy constitutes a colossal optical system—a cosmic camera obscura :

Literally “dark chamber”: Pre-photographic device projecting inverted images. It is a good metaphor for Iran’s political theology. Iran itself is this camera—not a geographic entity but the Shah’s shadow given spatial form or shadow: Corbin’s mundus imaginalis—Iran as metaphysical projection rather than territory. Persian literature crystallizes this: sāya (shadow) semantically knots together father, king, mercy, tent, and homeland.

The mirror that also appears frequently in Persian poetry and Sufi thought, serves the shadow as an anti-light. In cinema, the screen can be seen as such a mirror, showing not reality itself, but a reflection shaped by the filmmaker’s choices. Iranian cinema often carries a double consciousness aware both of the seen image (the bone) and of the unseen source (the spirit). Filmmakers like Aslani lean toward evoking the unseen through voice and sound, while others, like Kiarostami, let the visible image bear the weight of meaning.

Cinematic Poets: The Echo of Arslani and the Narcissus of Kiarostami

If we consider Arslani and Kiarostami as two poets—one who chose the language of cinema, the other the language of film—we can draw the echo and Narcissus analogy. To understand Arselani’s Echo-like nature, one need only listen to the repetition of voices in his films—an unseen voice, echoing endlessly. A voice that demands to be seen. Kiarostami, on the other hand, is someone for whom cinema is film itself. In the Lumière and Company project—where Kiarostami joined 40 international filmmakers in crafting 52-second films using the original Lumière camera—his work stands apart. His film? The story of two eggs frying: the sizzle of oil in a pan. A telephone answering machine’s beep at the start and end.

Like a bookbinder in love with the smell of paper and glue, or a typesetter enamored with lead type, Kiarostami is in love with film itself—the actual celluloid strip. The logic of his short film is tactile, material. He has slipped between the skin and the shirt of the filmstrip itself. What unfolds here is the burning of a film that does not burn—the melting oil in the pan simulating the film’s own combustion under the projector’s heat.

Lumière and Company (1995, original title “Lumière et Cie”)

A film in love with itself, burning eternally in an unreal flame. This is Narcissism. In this film, sound is enslaved to the image. The crackling oil does not command us to turn our heads to seek its source—rather, it rises from the image itself, luring us deeper into the frame. Just as Narcissus was drawn into the water’s mirror.

- Esmaeilpour Ghoochani, Iraj. (2012). Cinema is a Film: In the Phenomenology of the Spirit of Iranian Cinema. Anthropology and Culture. Retrieved from: https://vista.ir/w/a/21/kbey4

- “عیسی دم” (Jesus-breath): A Sufi metaphor for divine animation—referencing both Christ’s life-giving breath (Quran 3:49) and the wine-intoxicated sigh of mystical ecstasy. The “mold” (قالب) suggests both bodily form and a sculptor’s cast awaiting spirit. عظم رمیم (“rotten bones”) symbolizes mortal fragility, contrasting with the eternal “shadow” of the divine.

- Hegel’s phrase appears in the Physiognomy section, reducing absolute spirit to its most absurd materialist extreme. The shock-value lies in asserting identity between transcendental consciousness and inert matter.

- Following Hegel’s logic: the bone, when placed within the field of spirit, evolves into the form and direction of a skull. Therefore, spirit itself must be something like a bone—a skull. The original German passage reads:

“Die Wirklichkeit und Dasein des Menschen ist sein Schädelknochen… Wenn das Sein als solches oder Dingsein von dem Geiste prädiziert wird, so ist darum der wahrhafte Ausdruck hiervon, dass er ein solches wie ein Knochen ist.”

Translation: “The reality and concrete existence of man is his skull-bone… When Being as such or thingness is predicated of Spirit, the authentic expression of this is that Spirit is a thing like a bone.”

(Hegel, G.W.F., Phänomenologie des Geistes, Ullstein, 1973, pp. 180–202) - This mirrors the Persian concept of “روان” (ravān, psyche) as fluid spirit contained in the cranial “bowl” (کاسه سر). The skull becomes a wine-cup shaping its own intoxicating content—a material vessel that paradoxically generates the spiritual.

- Homa: The mythical Persian phoenix whose shadow confers sovereignty. Its real counterpart, the ossifrage vulture, performs a materialist inversion of this myth.

- Corbin’s analysis of Zoroastrian “exile in time”: Iranians await the Homa’s redemptive shadow as counter to Ahriman’s darkness.

Corbin, H. (1983). Cyclical Time & Ismaili Gnosis (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003209560 - Keshavarz Afshar, Mehdi. (2007). Tahlil-i tasavir-i Shahnameh az mazamin-i ostoure-i ta tarikh-i ejtemaii moaser. In: Catalogue of the First Symposium on Visual Anthropology. Chairman: Iradj Esmailpour Ghouchani. Faculty of Social Sciences, Tehran University.