The Paradox of Zoleikha: Near Yet Distant

From Metonymy to Metaphor

Iraj E. Ghoochani

This working paper explores Lacan’s Seminar XIII, Session 7, through the figure of Zoleikha, the wife of Potiphar in Islamic accounts. Drawing on Lacanian concepts of demand, desire, and topological structures like the torus, it examines her obsessive love for Joseph as a paradoxical shift from metonymy to metaphor. Insights from Rumi’s poetry and Islamic folklore illuminate the complex, inversive dynamics of her desire.

Zoleikha’s obsessive love for Joseph transforms everything in her world into him; his name: Joseph. Rumi expresses this in a line,

آن زلیخا از سپندان تا به عود نام جمله چیز یوسف کرده بود

(Zoleikha, from incense to aloe wood, turned the name of everything into Joseph). This is a shift from the specific to the universal: Joseph becomes a metaphor for her entire reality. Her experience embodies a process where metonymy—signifiers that are part of a chain representing the desired demanded object communicated through the practical language (I want this, I want hat, etc.)—transforms into metaphor, where one signifier (Joseph) comes to be everything.

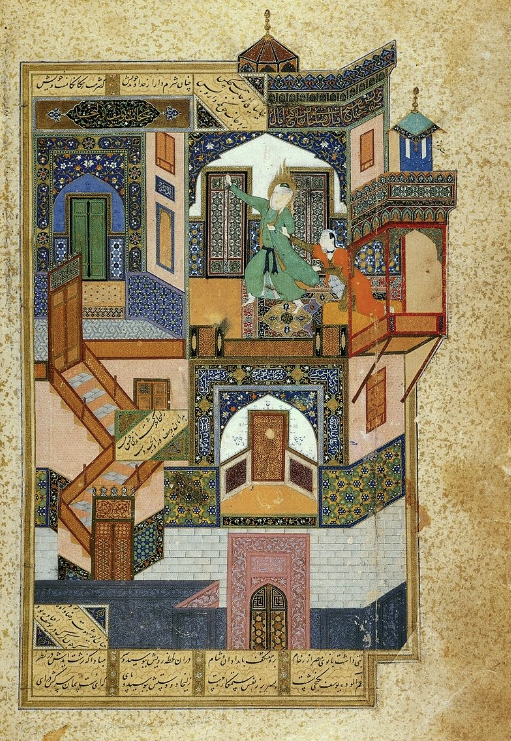

Kamal al-Din Behzad – The Flight of Joseph from Zoleikha (893 AH). This painting vividly illustrates the architectural complexity of Zoleikha’s palace, reflecting the multifaceted nature of her desire. The intricate design of the palace, with its zigzagging stairs and geometric patterns, embodies the labyrinthine journey Joseph must navigate to evade Zoleikha’s advances. The vibrant use of color—emerald green and cinnabar red—serves as a visual metaphor for the contrasting qualities of Joseph’s purity and Zoleikha’s sensuality. Behzad’s portrayal underscores the transformation of Zoleikha’s desire into a complex, almost architectural structure, where her yearning manifests through the elaborate and obstructive pathways Joseph must traverse: a profound visual counterpart to Zoleikha’s shift of demand into a her ultimate object of longing: desire.

The paradox here lies in the phantom nature of the object. Joseph is unattainable, yet omnipresent in her world. His absence becomes the very presence that fills her reality. This transformation from metonymy to metaphor perpetually deferred within the folds of language as being (Dasein).

Our desire is orthogonal to our demands. Lacan distinguishes between demand and desire: demand is a call for something specific, but as it is continuously expressed and denied, it can take the features of our desire, which revolves around a fundamental lack. Zoleikha’s longing for Joseph follows this trajectory. Initially, she demands Joseph in a concrete sense, but as her demand is unmet, it shifts into a more abstract, unending desire.

In Lacan’s theory, desire is self-generating and insatiable (like dropsy?) because it is structured around the absence of its very object. Zoleikha’s desire for Joseph yield to her secretive language, where every mundane object becomes an allusion to him. Is this not the story of initiation of every language including those secretive? This illustrates the endless folding of desire, where the more she speaks of him indirectly, the more elusive he becomes, leading her desire to long spirally even further onto its infinite expand.

The Infinite Folding of Desire and the Torus

The qualitative folding of Zoleikha’s desire, where each fold represents a new displacement of her love for Joseph, tends towards infinity. This infinite folding, where each fold deepens the space of her desire without ever arriving at its object: a circular, self-sustaining, surface without a clear beginning or end. As such, Zoleikha’s love for Joseph can be likened to a journey through the torus. Zoleikha’s desire for Joseph reflects the narcissistic entrapment. She becomes trapped in a form of a mirror licking figure like Master Adam in Dante’s inferno-Canto 30: desiring the unattainable reflection of Joseph but never being able to possess him. Her longing mirrors the torment of Master Adam’s dropsy: a demand growing beyond proportion and possibility. In this context, Joseph’s coat, torn from behind, symbolizes the impossibility of fully grasping the desired object. Zoleikha attempts to seize Joseph from behind, but this only reinforces the phantasmatic nature of her desire. In the Islamic folkloric retellings of the story, Zoleikha eventually becomes old and unattractive, but Joseph restores her youth and beauty by placing his coat over her head but this happens first at the most end of the story. This symbolic act suggests a kind of (instrumental?) convergence: her repeated demand finally finds spiritual resolution that affects and transforms her physical body, rather than through the physical possession she initially sought.

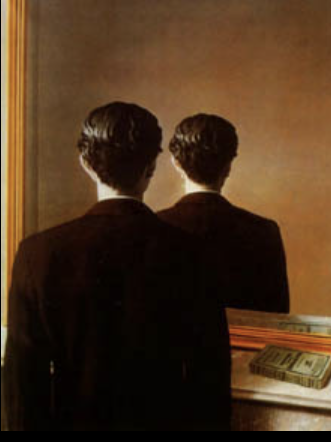

Left: René Magritte – Not to Be Reproduced (1937); Right: Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, Old Testament, by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, 1860. Encapsulating the paradox of being near yet distant, where the reflection of the back of the man’s head in the mirror signifies an unattainable self-awareness. This visual paradox parallels the tear in Joseph’s coat in the story of Zoleikha. The coat’s tear, positioned at the back, embodies the elusive and unattainable nature of Zoleikha(’s desire). Just as the mirror’s reflection provides a view of the back of the head—forever out of reach—so does the tear in the coat signify the continuous distance between Zoleikha and her ultimate object of desire: An absolute tension between proximity and unattainability.